Hi, and welcome to Comics You Should Own, a semi-regular series about comics I think you should own. I began writing these a little over fifteen years ago, and I’m still doing it, because I dig writing long-form essays about comics. I republished my early posts, which I originally wrote on my personal blog, at Comics Should Be Good about ten years ago, but since their redesign, most of the images have been lost, so I figured it was about time I published these a third time, here on our new blog. I plan on keeping them exactly the same, which is why my references might be a bit out of date and, early on, I don’t write about art as much as I do now. But I hope you enjoy these, and if you’ve never read them before, I hope they give you something to read that you might have missed. I’m planning on doing these once a week until I have all the old ones here at the blog. Today we’re looking at the Garth Ennis run on Hellblazer. This post was originally published on 8 July 2008. As always, you can click on the images to see them better. Enjoy!

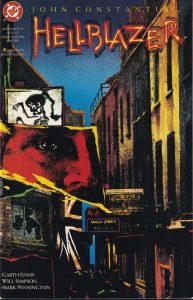

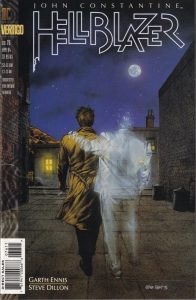

Hellblazer by Garth Ennis (writer), Will Simpson (penciller, issues #41-47, 50, 52-55, 59-61, 75), Mike Hoffman (penciller, issue #48), Steve Dillon (artist, issues #49, 57-58, 62-76, 78-83, Special #1), David Lloyd (artist/colorist, issue #56), Peter Snejbjerg (artist, issue #77), Mark Pennington (inker, issues #41-42, 46), Malcolm Jones III (inker, issues #43), Tom Sutton (inker, issues #44-45), Mark McKenna (inker, issue #46), Kim DeMulder (inker, issues #46, 59-60), Stan Woch (inker, issues #46-48), Mike Barreiro (inker, issue #59-61), Tom Ziuko (colorist, issues #41-50, 52-55, 57, 59-69, 71-83, Special #1), Daniel Vozzo (colorist, issue #58), Stuart Chaifetz (colorist, issue #70, 75), Gaspar Saladino (letterer, issues #41-50, 52-55, 57-66, 68-71, 73-74, Special #1), Elitta Fell (letterer, issue #56), Todd Klein (letterer, issue #67), and Clem Robins (letterer, issue #72, 75-83).

Published by DC/Vertigo, 43 issues (#41-50, 52-83, and Hellblazer Special #1, which comes between issues #71 and 72), cover dated May 1991 – November 1994.

As usual, SPOILERS play a large part of this post. Be warned!

When I wrote about the Top 100 runs [Edit: here’s the link!], I claimed I would put Ennis’s run on Hellblazer above Preacher. Now that I’ve re-read his run on Hellblazer, I may have to retract that statement.  Of course, I’ll have to see how I feel about Preacher once I get to it.

Of course, I’ll have to see how I feel about Preacher once I get to it.

It’s not that I don’t like this run. I think they are Comics You Should Own, after all. But there are problems with the run, and they make this, instead of a truly great comic, more of a comic that is far more interesting to read in order to dissect it and what’s wrong and right with it. It’s certainly “better” than several comics I’ve looked at in this column, but its ambitions are also much higher, and therefore we must hold it to that standard.

Ennis was 21 (!) when his first issue on this title came out, and that’s part of the problem. This is a young man’s comic masquerading as a more mature work. I often have an issue with older people trying to write young people and teenagers and failing miserably, but Ennis goes the opposite way. His John Constantine, who turns 40 in the middle of the run (and that issue, interestingly enough, acts as a moral fulcrum for the run), is written oddly, as if he’s desperate to be taken seriously but is often caught prancing around playing dress-up, because he’s so immature. This is true when Ennis wants it to do it deliberately, as he often does (Constantine is immature, which is part of what makes him so charming), but it also comes through in the heavy-handed writing style and when Ennis wants to write “mature” adults. Ironically, the only times he really does a good job with portraying adults is when he writes certain women, Kit Ryan included. It’s this difficulty with Constantine – both deliberate and accidental – that makes much of this series tough to swallow. We’re never supposed to really like John, after all, because he is, as he often narrates, the kind of person who leaves his friends to die.  But in much of this run, we not only dislike John but find him ridiculous, and we get the distinct feeling that Ennis wasn’t going for that.

But in much of this run, we not only dislike John but find him ridiculous, and we get the distinct feeling that Ennis wasn’t going for that.

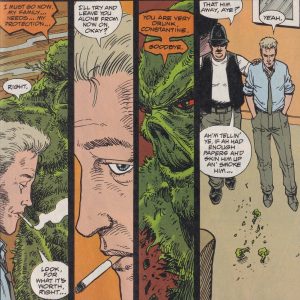

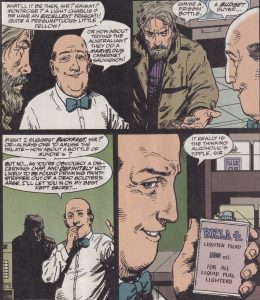

Part of the problem is that Ennis is torn between writing straight horror, a cultural critique, and an examination of friendship. He is very good at quiet moments between people who care about each other but can’t necessarily get along, as he shows in later works. In Hellblazer, he began that tradition, and those are the best issues or moments in the run. Ennis tends to overdo the drinking in this comic without really pointing out that Constantine is an alcoholic, but when his characters sit down and talk, it’s often brilliant, because the people speak like real people without falling into Bendis-like stuttering. He starts this early on, as in issue #42 John visits Brendan Finn, who is drinking himself to death. This is part of Ennis’s first story arc, “Dangerous Habits,” the famous one in which John finds out he’s dying of lung cancer. In #42, John figures out a way to cheat the Devil of Brendan’s soul (Brendan having sold his soul to amass the greatest collection of alcohol ever), earning him the enmity of that particular evil entity and shaping the run in general, as Satan schemes to figure out a way to take John to Hell (especially after John cheats him of his own soul in issue #45). Before the confrontation with Satan, though, John and Brendan talk about their lives and the choices they’ve made. Brendan, interestingly enough, becomes a key figure in John’s life, even though he’s dead early on. He shows up later as a ghost, and we also get a flashback to when John first met Kit, back when she was with Brendan.  This kind of issue, where John talks to friends of his (and issue #70, “Heartland,” which doesn’t feature John at all, instead showing Kit back in Belfast getting re-integrated into her world), make us realize what an excellent writer Ennis is. It’s very hard to make conversations in comics compelling, but Ennis manages it.

This kind of issue, where John talks to friends of his (and issue #70, “Heartland,” which doesn’t feature John at all, instead showing Kit back in Belfast getting re-integrated into her world), make us realize what an excellent writer Ennis is. It’s very hard to make conversations in comics compelling, but Ennis manages it.

Hellblazer is a horror comic, though, so Ennis can’t simply write stories about John and the way he grows up throughout the run. His plots, for the most part, are excellent. The way they play out aren’t always, but the premise of the run and the individual plots are superb. Let’s break them down quickly:

Issues #41-46: “Dangerous Habits.” John finds out he has lung cancer from smoking all those Silk Cut for so many years, and he doesn’t want to die, naturally. So he concocts a brilliant scheme in which he sells his soul to two different demons even though Satan already has a claim on it. With three competing claims, the demons have no choice but to heal his disease and keep him alive, lest a war in Hell erupt.

Issues #47-48: A two-part ghost story in which deceased pub owners take some nasty revenge on those who killed them.

Issue #49: The Christmas issue, an odd cross-“Vertigo” theme for that month (Vertigo didn’t exist yet, but Swamp Thing, Doom Patrol, and Shade all had Christmas-themed issues).  Ennis introduced the Lord of the Dance, a pre-Christian deity who’s bummed out because no one drinks anymore. Well, until John shows him differently.

Ennis introduced the Lord of the Dance, a pre-Christian deity who’s bummed out because no one drinks anymore. Well, until John shows him differently.

Issue #50: John meets the King of the Vampires. An almost perfect example of the best and worst of the run, as the execution is very clever, but the writing is often overwrought.

Issues #52-55: “Royal Blood.” After a guest writer in #51 (and a creepy tale set in a laundromat), this is a story of a member of the royal family (Prince Charles, most likely, although he’s never named) being possessed by a demon and going on a killing spree. Charming stuff.

Issue #56: The story of a man haunted by his diary. One of the more horrifying of the run.

Issues #57-58: John and Chas try to find out why Chas’s uncle’s body was stolen from its grave. It ain’t pleasant.

Issues #59-61: “Guys and Dolls.” Ellie, a demon John knows, comes to him with a problem: Satan is after her. He helps her hide, but she owes him one. Well, two really, as we find out how John helped her a decade earlier. And he collects on both debts, big-time, later.

Issue #62: John and Kit visit John’s sister Cheryl, who tells him that his niece, Gemma, is experimenting with magic. Kit talks to her, while John tracks down the kid who got her into it. It’s another very good issue about John’s family and its history and what Kit means to him.  It also includes one of the best sentences in the run: “And there’s just a tiny murder in the night.”

It also includes one of the best sentences in the run: “And there’s just a tiny murder in the night.”

Issue #63: John’s fortieth birthday. Another nice issue, guest-starring Zatanna and Swamp Thing.

Issues #64-66: “Fear and Loathing.” John gets involved in politics, as the National Front, a racist organization, makes a move on him. Meanwhile, the angel Gabriel, who has been hanging out with the racists, begins to question God’s plan, which has pretty bad consequences for him.

Issue #67: Kit leaves John because he couldn’t keep his shenanigans out of her life. He then freaks out at Chas, burns all his bridges, and drinks himself into a stupor.

Issues #68-69: Living on the street, John is found by the King of the Vampires. Even drunk, John is more than a match for him.

Issue #70: Kit gets re-acquainted with her friends in Belfast. A brilliant issue, as I mentioned above.

Issue #71: John hallucinates about a World War II fighter pilot, and it’s enough to get him back on his feet. Another good issue, and an early example of Ennis’s love of war comics.

Hellblazer Special #1: John sees a man who once gave him a lift and tried to molest him, and the man tells him his story. This ties back into John’s continuing battle with Satan.

Issues #72-75: John visits New York and gets trapped in a strange dreamland by Papa Midnite, the antagonist from the earliest issues of the title.  This is probably the weakest story arc in the run.

This is probably the weakest story arc in the run.

Issue #76: On the way back to England, John makes a pit stop in Dublin and meets Brendan Finn’s ghost. More reminiscing about the old days, and we find out how more of John’s friends died.

Issue #77: Chas tells a story about John and a strange exorcism. Another strong standalone issue.

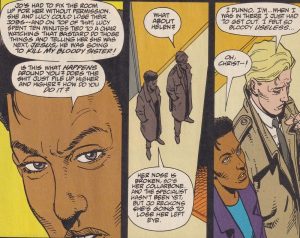

Issues #78-83: “Rake at the Gates of Hell.” Satan figures out how to hurt John, and he proceeds to cut a swath through his friends. Just for fun, there’s a race riot in London, and John tries to get an old friend off heroin. An impressive ending to the run.

These plots are interesting not necessarily because of their execution, although Ennis usually does well with planning them out and tying up the loose ends. They’re interesting because of what they tell us about the comic itself and what Ennis is really doing. Consider the actors in these plots and what they’re doing. In the first arc, John is trying cure his lung cancer, and does. This doesn’t stop him from smoking, naturally, especially because he now believes himself to be invincible. After this, he gets into problems almost solely of his own design, with “Royal Blood” and the issues he has with the National Front the only exceptions. Everything that follows in the run is from his problems with smoking and how he “solves” it. This leads us to a fascinating conclusion about the run in general: it’s almost all about addiction.

Consider: John is addicted to smoking. He’s also an alcoholic. Out of 43 issues, 24 of them show John (or, in the case of #70, Kit) drinking in some way or another. That may not seem like a lot, but it’s over half and far more drinking than we usually see in a comic.  John’s smoking causes problems, but except for issues #67-71, Ennis doesn’t show any problems his drinking causes him, and after he decides to live in issue #71, it’s never a concern again. In issue #71, John thinks, “You never gave up. You knew the precious thing you had, and you scraped and clawed and fought to the last drop of blood for life –” He’s thinking about the fighter pilot whose skeleton he has uncovered, who didn’t give up even though his plane was shot to pieces. It’s an inspiring speech, but alcoholism isn’t overcome by pretty speeches about how great life is. John is an addict, but in more ways than one. He’s not only addicted to alcoholism, he’s addicted to the rush of magic. When we read this run, we always have to remember that DC had a vested interest in making sure Constantine doesn’t change, just like all their other characters, but it’s fascinating to read as Ennis sets up two sides of John’s life: the one we know, and the one with Kit. Kit constantly reminds him to keep the magic part of his life separate from their relationship, and she leaves him because he can’t. He has a wonderful relationship, but he can’t turn away from screwing around in his life. Of course, he has a reason for it, on the one hand – he knows Satan is coming after him, and a great deal of what he does in the run is in preparation for their final showdown. It’s ironic that the situation in which Kit is threatened has very little to do with John’s problems with Satan. Even Kit can’t keep John away from messing around. His love is not strong enough.

John’s smoking causes problems, but except for issues #67-71, Ennis doesn’t show any problems his drinking causes him, and after he decides to live in issue #71, it’s never a concern again. In issue #71, John thinks, “You never gave up. You knew the precious thing you had, and you scraped and clawed and fought to the last drop of blood for life –” He’s thinking about the fighter pilot whose skeleton he has uncovered, who didn’t give up even though his plane was shot to pieces. It’s an inspiring speech, but alcoholism isn’t overcome by pretty speeches about how great life is. John is an addict, but in more ways than one. He’s not only addicted to alcoholism, he’s addicted to the rush of magic. When we read this run, we always have to remember that DC had a vested interest in making sure Constantine doesn’t change, just like all their other characters, but it’s fascinating to read as Ennis sets up two sides of John’s life: the one we know, and the one with Kit. Kit constantly reminds him to keep the magic part of his life separate from their relationship, and she leaves him because he can’t. He has a wonderful relationship, but he can’t turn away from screwing around in his life. Of course, he has a reason for it, on the one hand – he knows Satan is coming after him, and a great deal of what he does in the run is in preparation for their final showdown. It’s ironic that the situation in which Kit is threatened has very little to do with John’s problems with Satan. Even Kit can’t keep John away from messing around. His love is not strong enough.

What makes Kit and John’s relationship interesting is that she herself is an enabler, to a certain degree. When she breaks it off with him, she says, “I don’t want you to be perfect. I just want a quiet life without some bastard kicking my door down and coming at me with a switchblade.”  A not unreasonable request, you might think. Then, when he’s about to leave, she tells him, “You’re a stupid, selfish bastard, John. And you’ve never really cared about anyone.” Of course she’s right and wrong, because he does love her, but not completely. She’s in the wrong, too, and Ennis makes this point rather subtly (one of the few times he ever does things subtly, I know): Kit never asks him to choose. She made all the compromises in the relationship, and although I know what we would have gotten if she had issued an ultimatum – a lot of whining from both John himself and the fanbase that “she just doesn’t get him” and that changing would destroy what she loves about him in the first place – an adult relationship requires compromise from both parties. Most relationships, it seem, fall apart because one or both parties are not willing to do that. Kit never asks him to change anything. She doesn’t want him shitting where he lives, but that’s not the same thing. She simply allows John to carry on with what he’s doing even though it makes her uncomfortable and she’d already been in a relationship – with Brendan – where the man refused to change and eventually died because of it. She accepts him as he is, and as noble as that is, maybe John does need to change. This is hammered home in issue #82, when Kit returns. It’s another wonderfully written issue, and even though John promises to give it all up for her, she sees right through him. She tells him a story about Brendan drinking himself to death and how noble he thought it was and how she sees John doing the exact same thing. Then she and John have a good-bye fuck, and we’re supposed to believe that she’s leaving him for the last time. But the point is: John is too charming. Kit came back, and there’s no reason to think that she won’t again. John might not get the love of a good woman, but he doesn’t want that anyway.

A not unreasonable request, you might think. Then, when he’s about to leave, she tells him, “You’re a stupid, selfish bastard, John. And you’ve never really cared about anyone.” Of course she’s right and wrong, because he does love her, but not completely. She’s in the wrong, too, and Ennis makes this point rather subtly (one of the few times he ever does things subtly, I know): Kit never asks him to choose. She made all the compromises in the relationship, and although I know what we would have gotten if she had issued an ultimatum – a lot of whining from both John himself and the fanbase that “she just doesn’t get him” and that changing would destroy what she loves about him in the first place – an adult relationship requires compromise from both parties. Most relationships, it seem, fall apart because one or both parties are not willing to do that. Kit never asks him to change anything. She doesn’t want him shitting where he lives, but that’s not the same thing. She simply allows John to carry on with what he’s doing even though it makes her uncomfortable and she’d already been in a relationship – with Brendan – where the man refused to change and eventually died because of it. She accepts him as he is, and as noble as that is, maybe John does need to change. This is hammered home in issue #82, when Kit returns. It’s another wonderfully written issue, and even though John promises to give it all up for her, she sees right through him. She tells him a story about Brendan drinking himself to death and how noble he thought it was and how she sees John doing the exact same thing. Then she and John have a good-bye fuck, and we’re supposed to believe that she’s leaving him for the last time. But the point is: John is too charming. Kit came back, and there’s no reason to think that she won’t again. John might not get the love of a good woman, but he doesn’t want that anyway.  If he did, he really would do what he promised and ditch it all for her. Of course, given that Kit was Ennis’s pet character, she doesn’t come back, but the way Ennis writes it, we don’t necessarily believe she’s gone for good.

If he did, he really would do what he promised and ditch it all for her. Of course, given that Kit was Ennis’s pet character, she doesn’t come back, but the way Ennis writes it, we don’t necessarily believe she’s gone for good.

An interesting parallel to Kit is Sarah, the woman John is sleeping with at the beginning of “Rake at the Gates of Hell.” We know nothing about her, and before we can find anything about their relationship, John asks her for a favor. He sees an old friend, Helen, who’s a hooker strung out on heroin. In order to keep her away from her pimp, he asks Sarah to set something up privately with her sister, who’s a nurse. He can’t take her to a hospital, because the police will get involved, and her pimp could find her too easily. Of course, it all goes to hell, because her pimp does find her, and although no one dies, Helen ends up in the hospital anyway, and John can’t do anything except hire some thugs to beat the shit out of the pimp. Sarah doesn’t put up with John’s crap like Kit did for too long. John can’t face Helen in the hospital, and when he asks Sarah if Helen’s pimp raped her, Sarah lights him up:

Why? Isn’t it bad enough for you yet? … You really are something, d’you know that? You want it that way so it’s really bad! So you can get good and angry enough to go out there and commit whatever atrocity you’ve got in mind for that guy! It won’t help Helen one bit — but you don’t care because you know you’re no good at helping her anyway! ‘Cos all you’ve got left in your frigging revenge!! I’ve got news for you, chum! The reason you felt useless in there is because you are! You’re like every other stupid macho bastard I’ve known: You can’t think with anything except your dick or your fists! You think you know it all! You think you’re trying to help! And all you’re doing is making things worse!!

She shouts this last line as John flees from the hospital, and it’s the mark of a complete coward that John runs from her and goes right out and does what she accuses him of – finding the pimp and making sure he gets beaten.  It’s a devastating attack on our hero, because even though he has always left his friends to die and is therefore not a terribly sympathetic character, he (and the audience) always justifies it because he’s doing it for the greater good. Even in this situation, he’s doing it for Helen, but he’s not willing to put in the work to make sure Helen is okay. He leaves the dirty work to Sarah’s sister and another nurse, both of whom (along with Helen) pay far more than John does. Why? Because he’s addicted to being the “hero,” the white knight who saves people but doesn’t want to soil his armor. Yes, he often gets down and dirty in his schemes, but John makes sure that someone else always suffers more. It’s a disturbing idea to consider, because we want to admire John. Ennis doesn’t allow us to. John is an addict, and addiction is never pretty or admirable.

It’s a devastating attack on our hero, because even though he has always left his friends to die and is therefore not a terribly sympathetic character, he (and the audience) always justifies it because he’s doing it for the greater good. Even in this situation, he’s doing it for Helen, but he’s not willing to put in the work to make sure Helen is okay. He leaves the dirty work to Sarah’s sister and another nurse, both of whom (along with Helen) pay far more than John does. Why? Because he’s addicted to being the “hero,” the white knight who saves people but doesn’t want to soil his armor. Yes, he often gets down and dirty in his schemes, but John makes sure that someone else always suffers more. It’s a disturbing idea to consider, because we want to admire John. Ennis doesn’t allow us to. John is an addict, and addiction is never pretty or admirable.

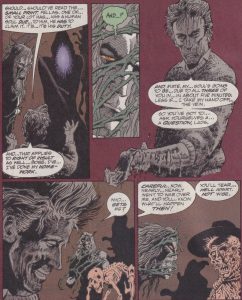

What’s interesting about this is that so many other characters in this run are addicted, too. The major antagonist of Ennis’s Hellblazer is the Devil, and his obsession with Constantine is addictive and blinds him to what causes his downfall. Of course, pride is the deadly sin that Satan is usually pinned with (this isn’t Lucifer, as this was back when the “Vertigo” books still maintained some continuity, so there are several references to Lucifer giving up his throne to Hell, an event that occurred in Sandman), and in this book, pride is what causes both John’s and Satan’s problems.  Satan is so sure that John belongs to him in “Dangerous Habits” that he ignores the trap John sets for him, and in “Rake at the Gates of Hell,” he misses the fact that someone close to him is betraying him. Papa Midnite, the other main antagonist in the run, is also so blinded by hatred of Constantine that he too misses someone close to him betraying him (interestingly, both traitors are women). Satan has only himself to blame for his predicament – John tricks him, in issue #42, into drinking holy water, and Brendan Finn’s soul escapes Hell because of it. In classic James Bond villain mode, Satan is so sure that he can’t be touched that he allows himself to gloat, and you never gloat if you’re a villain! His addiction to revenge ultimately costs him, and it’s interesting to consider how little difference there is between the Devil and John himself. Ennis doesn’t exactly make it subtle, but it’s interesting because we’re conditioned to think of Satan as, well, evil, while John is supposedly “good.” But their final conversation is revelatory, not because of what Ennis thinks of the Devil’s relationship with God (this is the first reference in Ennis’s fiction of God as a drooling, masturbatory madman, but it won’t be the last), but because of how John sees exactly what Satan is. The Devil says, “But ever since I fell, I’ve wondered down the eons what he meant for me … What sense of purpose dredged me from within that mind …? What the point of someone he could talk to, if he wouldn’t even listen? And that has torn at me since –” John interrupts with “You’re his conscience.” This strikes John as funny, and Satan loses it, saying something John himself might say: “Don’t you laugh at me, you little bastard! I tried to make it better!” At the end, John is the same – he tries to make it better, and it usually turns to shit. But John has one more friend than the Devil, and that’s why he wins. But that doesn’t mean he’s any better than the Devil himself.

Satan is so sure that John belongs to him in “Dangerous Habits” that he ignores the trap John sets for him, and in “Rake at the Gates of Hell,” he misses the fact that someone close to him is betraying him. Papa Midnite, the other main antagonist in the run, is also so blinded by hatred of Constantine that he too misses someone close to him betraying him (interestingly, both traitors are women). Satan has only himself to blame for his predicament – John tricks him, in issue #42, into drinking holy water, and Brendan Finn’s soul escapes Hell because of it. In classic James Bond villain mode, Satan is so sure that he can’t be touched that he allows himself to gloat, and you never gloat if you’re a villain! His addiction to revenge ultimately costs him, and it’s interesting to consider how little difference there is between the Devil and John himself. Ennis doesn’t exactly make it subtle, but it’s interesting because we’re conditioned to think of Satan as, well, evil, while John is supposedly “good.” But their final conversation is revelatory, not because of what Ennis thinks of the Devil’s relationship with God (this is the first reference in Ennis’s fiction of God as a drooling, masturbatory madman, but it won’t be the last), but because of how John sees exactly what Satan is. The Devil says, “But ever since I fell, I’ve wondered down the eons what he meant for me … What sense of purpose dredged me from within that mind …? What the point of someone he could talk to, if he wouldn’t even listen? And that has torn at me since –” John interrupts with “You’re his conscience.” This strikes John as funny, and Satan loses it, saying something John himself might say: “Don’t you laugh at me, you little bastard! I tried to make it better!” At the end, John is the same – he tries to make it better, and it usually turns to shit. But John has one more friend than the Devil, and that’s why he wins. But that doesn’t mean he’s any better than the Devil himself.

This idea of addiction is wedded to the other main theme of the book, which is the use and abuse of power. This isn’t a terribly original theme, as most mainstream comic books have some element of the idea of power and how the powerful abuse it (perhaps because most mainstream comic books are written by men, who seem to have an unhealthy obsession with power, but that’s a theory for another day), but that doesn’t stop Ennis from exploring it through the prism of addiction.  Naturally, power is addictive in this book, as it is most places, and what’s fascinating about Ennis’s thoughts on power is that the more Constantine has, the less in control he seems to be. This is reflected throughout the book with almost every character. Constantine is always at his best when he has a plan that goes awry and people are dying around him and he needs to pull something out of his ass. Ennis suggests that this chaotic way of dealing with life is more ideal (certainly it’s more interesting, fictionally) than those people who cling to the illusion of power. Satan, of course, is the obvious example of someone whose lust for power blinds him to everything else. Not only does he allow his addiction to “getting” John obscure his vision, but his desire to control everything allows someone who promises that control get close to him and ultimately betray him. Papa Midnite, as we’ve seen, is the same way. But there are other powerful people in the book, and Ennis delights in showing us how powerless they really are. The King of the Vampires, who appears twice, is the classic example – in issue #50, John asks a fantastic question of him: “And just so we’re sure who’s better off, why don’t we sit here together and watch the sun come up in an hour or so?” John has his weaknesses, sure, but he knows what they are and can live with them. The King of the Vampires can’t. Ennis, like most writers, enjoys taking the powerful down a peg, but what’s so compelling about this is that Constantine can’t really match power for power. He gets by on guile, and those very few times he has power, he loses it quickly. This is most evident in the final storyline, when he deals with Helen. He is in command with her for most of the time, and when her pimp beats her up again, John responds by using what power he has and destroying the pimp.

Naturally, power is addictive in this book, as it is most places, and what’s fascinating about Ennis’s thoughts on power is that the more Constantine has, the less in control he seems to be. This is reflected throughout the book with almost every character. Constantine is always at his best when he has a plan that goes awry and people are dying around him and he needs to pull something out of his ass. Ennis suggests that this chaotic way of dealing with life is more ideal (certainly it’s more interesting, fictionally) than those people who cling to the illusion of power. Satan, of course, is the obvious example of someone whose lust for power blinds him to everything else. Not only does he allow his addiction to “getting” John obscure his vision, but his desire to control everything allows someone who promises that control get close to him and ultimately betray him. Papa Midnite, as we’ve seen, is the same way. But there are other powerful people in the book, and Ennis delights in showing us how powerless they really are. The King of the Vampires, who appears twice, is the classic example – in issue #50, John asks a fantastic question of him: “And just so we’re sure who’s better off, why don’t we sit here together and watch the sun come up in an hour or so?” John has his weaknesses, sure, but he knows what they are and can live with them. The King of the Vampires can’t. Ennis, like most writers, enjoys taking the powerful down a peg, but what’s so compelling about this is that Constantine can’t really match power for power. He gets by on guile, and those very few times he has power, he loses it quickly. This is most evident in the final storyline, when he deals with Helen. He is in command with her for most of the time, and when her pimp beats her up again, John responds by using what power he has and destroying the pimp.  It’s an ugly side to John, but it’s the best way Ennis can point out that power does corrupt, because the rest of the powerful in the book are already so corrupt he can’t make that point with them.

It’s an ugly side to John, but it’s the best way Ennis can point out that power does corrupt, because the rest of the powerful in the book are already so corrupt he can’t make that point with them.

Despite these very interesting themes, there is plenty wrong with Ennis’s Hellblazer. His brief forays into politics don’t work terribly well, because he doesn’t bring the same nuances to them as he does to the interpersonal relationships in the comic. “Royal Blood” is the main political story, and the “big idea” of the arc is that the demon possessing Prince Charles (or whoever it is) is no different than any other royal, because, as Peter Marston puts it, “What has our royal family ever done … except feed off the blood of the people?” It’s a fairly derivative idea, and the entire story, which is not an awful horror yarn, doesn’t really work as political commentary. In the other overtly political arc, “Damnation’s Flame,” John makes his way through an American nightmare landscape, and although the point Ennis makes about Kennedy and our obsession with him is valid (Kennedy, who becomes John’s spirit guide, says that the idealization of him has crippled the American body politic and kept us from moving on, which is true to a certain extent), his idea of America as a pimp and the rest of the world as whores isn’t particularly original or compelling (and, in hindsight, the country rising in the East ought to be China, not Japan), and the idea of the completely noble American Indian is childish and a bit insulting. “Rake at the Gates of Hell” has as a subplot the confrontation between the racist police and the inhabitants of a largely black housing project, and it works mainly because it’s about the characters, not about any grand political screed. The race riot begins because two cops try to bust George, an acquaintance of John’s, for marijuana dealing and his mother gets killed in the process. George freaks out, kills one of the cops, and things spiral from there. It’s less a political statement, even though Ennis manages to work politics into it. Earlier in the run, the evil racist Charlie Patterson, who sends punks to hurt Kit, which is the impetus for her to leave John, doesn’t even have a plan, really.  He says he does, but we never learn what it is. It’s probably for the best, as it’s not all that pertinent to the story, and it probably wouldn’t be terribly deep anyway. Ennis obviously wears his politics on his sleeve, but that’s not the best place to wear them if you’re going to write good political stories. It doesn’t hurt the run too much, but it does keep it from being as great as it could be.

He says he does, but we never learn what it is. It’s probably for the best, as it’s not all that pertinent to the story, and it probably wouldn’t be terribly deep anyway. Ennis obviously wears his politics on his sleeve, but that’s not the best place to wear them if you’re going to write good political stories. It doesn’t hurt the run too much, but it does keep it from being as great as it could be.

Ennis took a lot of the themes he explored in this comic and used them in his next two long-running series, Preacher and Hitman. Those books were a bit more mature than this, which is to be expected, but Hellblazer has one advantage in that readers knew what to expect from a John Constantine story, so when Ennis subverted those expectations, it worked in his favor. It has another advantage over Preacher: Ennis doesn’t turn the book into his personal soapbox as much as he does in the later comic. This keeps things moving along at a faster clip than in Preacher, which often grinds to a halt so Jessie and Cassidy can rant about whatever it is that bothers Ennis on that particular day. Despite that, Hellblazer has its faults, but that shouldn’t stop us from reading it and appreciating what Ennis did with John Constantine. He pulled back on some of the horror (not all, but some) and showed us a Constantine who was weak and a bit immature. He also gave John a reason to get out of the “business” in Kit, and the great tragedy of John’s life is that he is unable to change. Of course, this is the mandate of DC, because they want to keep publishing the adventures of Mr. Constantine, but Ennis, to his credit, makes this a profound character flaw in John, and it adds a level of sadness to the comic that wasn’t present before, even with all of John’s friends dying. When Header and Rick and Nigel die, it’s not because John was saving the world and sacrificing them in the process. It’s because he’s completely ineffectual and can’t stop it.  That’s a world of difference. Even Helen, who does get off smack thanks to John, tells him in the final Ennis issue, “I’m not sayin’ I’ll never end up whorin’ again, or even goin’ back to bein’ a smackhead, ’cause I haven’t a clue what’ll happen to me.” The tragedy of John Constantine is that he doesn’t care: he was her hero, and he isn’t interested in keeping her off the heroin or out of prostitution, because that’s where the hard work is – Helen has to do it for herself, of course, but it always helps if we have someone who cares. Ultimately, John got what he wanted – someone to tell him he’s okay, after so many others told him he was a shit. It allows Ennis to end his run on a high note, but it’s a false high note, and that’s what makes it more resonant.

That’s a world of difference. Even Helen, who does get off smack thanks to John, tells him in the final Ennis issue, “I’m not sayin’ I’ll never end up whorin’ again, or even goin’ back to bein’ a smackhead, ’cause I haven’t a clue what’ll happen to me.” The tragedy of John Constantine is that he doesn’t care: he was her hero, and he isn’t interested in keeping her off the heroin or out of prostitution, because that’s where the hard work is – Helen has to do it for herself, of course, but it always helps if we have someone who cares. Ultimately, John got what he wanted – someone to tell him he’s okay, after so many others told him he was a shit. It allows Ennis to end his run on a high note, but it’s a false high note, and that’s what makes it more resonant.

Ennis’s run has been collected in several different trade paperbacks: “Dangerous Habits,” “Bloodlines,” “Fear and Loathing,” “Tainted Love,” “Damnation’s Flame,” “Rake at the Gates of Hell,” and “Rare Cuts,” which has the standalone issue #56 along with a bunch of other stories by different writers. It’s an excellent run that shows what Ennis is capable of. And nobody has sex with a giant meat puppet, so that’s a plus.

Take a look at the archives, if you have some time to spare!

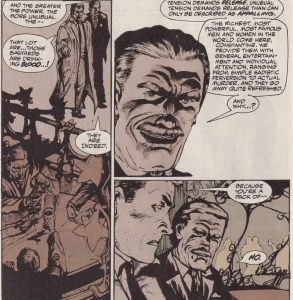

[Back in the day, I tended to focus on themes of these comics a bit more, mainly because I still wasn’t confident about writing about the art. I still try to write about themes, but I’m more confident about writing about art, so I do, because artists are a crucial part of comics. I don’t even mention Simpson and Dillon, the two main artists on this run, in this article, and for that I kind of suck. Simpson has an interesting, languorous style that owes more to the “Vertigo” sensibility – in this case, pre-Vertigo, more to the artists on Moore’s Swamp Thing than anything – that works for demons and such, as Simpson designs interesting weird things. He is not helped at all by Ziuko’s coloring, which, as you can see, tends toward the monochromatic. Dillon becomes the regular artist on issue #57, and Ziuko’s colors instantly become more diverse and “realistic,” so I’m not sure what he was doing with Simpson’s work. Dillon is Dillon, of course – a solid draughtsman who doesn’t dally in weirdness as much as Simpson, so even his more bizarre creatures feel grounded in a realism that helps with making John’s world a bit more gritty but doesn’t help with the odder stuff. Dillon is always the kind of artist who will do very solid work, but it never feels like he’s challenging himself or the reader. He does very good work with the conversations Ennis makes him draw, because he’s marvelous at small things in characters’ faces. He’s less successful with grand things, although he certainly doesn’t embarrass himself. Anyway, I suck because I didn’t write anything about the art, even though comics are, you know, a visual medium. My apologies!

It seems as though DC keeps these in print – I linked to the first volume of Ennis’s run below, and it appears there are other ways you can read it, too. It’s nice that DC is keeping these around, isn’t it? If you’re interested in these and haven’t read them, here’s where you start!]

Mr. Burgas: “Rake at the Gates of Hell” still remains my favorite X-mas songs to sing along with Christmas carolers. he he he

Didn’t know Ennis was 21 when he started HELLBLAZER. Hell, Morrison was a young turk when he started ANIMAL MAN/DOOM PATROL too.

Dunno if you’ve heard, but DC is getting around to the end of the HELLBLAZER tpb reprints with Vol. 26 and Vol. 24 and 25 should be out this year.

Tom: I’ve actually never heard Rake at the Gates of Hell. I should probably give it a listen.

I saw that DC was finishing the trades, but I own the Milligan run in single issues, so I won’t be getting them right now!

I finally got around to reading this run after years of hearing about how amazing it was and also being an Ennis fan, it was kind of a blind spot. It was good, bordering on great depending on the arc but I think there are much better runs from Mike Carey and Peter Milligan. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed it for all the reasons you stated but this is only HELLBLAZER run that seems to get any attention and that’s a shame.

DarkKnight: I have a feeling it was because it’s the first long run with the character, as Delano’s wasn’t as long and there were several interruptions. A lot of people copied the characterization of John from Ennis and not from Moore or Delano. I’ve never read the Carey stuff because I don’t love Carey, but I do like Milligan’s run quite a bit. I don’t know if it’s better than this because I haven’t re-read it yet, but I think it’s very good.

I’ve never forgiven Carey for his Ultimate Fantastic Four run.

And I never will.

So, so bad…and they got Pasqual Ferry on pencils!

Yup, I totally agree. It was almost painful to get through.

“With three competing claims, the demons have no choice but to heal his disease and keep him alive, lest a war in Hell erupt.”

I read this when it came out and even at 17, I thought this was a terrible ending. Clearly, his soul goes to whomever he sold it to first. Now, you could argue “well, they are devils and they wouldn’t play nice with each other and agree to that” but I still think that’s crap.

I imagine that’s the solution; the two others wouldn’t feel the need to recognize the primacy of the first claim. You just have to move right past it! 🙂

I must admit I liked the movie ending — John’s cancer takes him just as he’s saved the world so Satan cures him because John’s in a state of grace and will enter heaven. Leave him alive and he’ll sin again.

Ah, I love this run.

Wouldn’t quite put it at the same level as Preacher…but he was 21!!!

Haven’t read much other Hellblazer (I have read the Gaiman issue, and the not-great Ellis issues…but I really didn’t enjoy what I’ve read of Delano’s run, so I’m not compelled to read it start to finish, given how well this works as a stand-alone work), but I adore the cast Ennis sets up here…which makes Rake even more tragic (his priest friend…).

Man, I love the Lord of the Dance, as well – him showing up at the birthday party is a definite highlight.

Carlos: The only problem I have with any writer of Constantine is that they always set up a supporting cast and then basically kill everyone off, and Ennis set the precedent for that. Chas is the only one who survives and is still in the book, and it makes me wonder why anyone hangs out with John!

Phil Foglio made jokes about this in his Stanley and the Monster mini. A psychic approaches what he thinks is Constantine with a warning, but it turns out the unshaved, drunken, chain-smoking occultist is actually Ambrose Bierce. Who then quips that if he were Constantine, the psychic would be dead within minutes.

A great run by one of my favorite writers on one of my favorite characters…but not the best run on Hellblazer. I couldn´t really decide which writer was the best just that I like Andy Diggle`s run the “least best” (it´s good but kind of paint-by-numbers). I do believe that especially Paul Jenkins run is criminally underrated because it´s right between the two big names Ennis and..ahem..Warren Ellis.

To me there are four reasons why Ennis overshadows the other writers:

1. It´s the most accessible run and not very complicated.

2. The horror elements for a horror book are not that horrific after all. A bit of gore every once in a while but that´s it. Compared to Delano or Ellis fairly harmless.

3. Garth Ennis became so succesful later on.

4. There is so much humour in the book. When these issues came out I was in my early twenties and at least three of my friends also read Hellblazer. At every party we´d have discussions like” and then he pisses on a burning vampire” or “and then he smokes a joint made out of Swamp Thing” or “and then she stabs the Fascho in the crotch”.

On a personal note, the repeated Pogues references also helped making me love the book. Around that time was also my only Pogues concert (minus Shane McGowan, unfortunately).

One final note: Preacher, Hitman, Unknown Soldier, The Boys and some of Ennis´s War Stories (D-Day Dodgers and the one of the four guys stuck in a bomb crater in the Spanish Civil War – the use of that one name: Guernica!) are still better than this run.

And Greg: I was kidding about The Boys:-)

I’ve never been a huge fan of Jenkins’s run. It’s different, certainly, but something about it doesn’t click.

I think your reasons for this run being so popular are spot on.

I definitely found Ennis’s John more interesting than Delano’s, and there are some really classic comics in the run. That said, I do recall thinking that the story set in the US was just abysmal. Stories that attempt to explore the nature of a nation’s culture rarely thread the needle, and that one certainly didn’t.

I agree. Generally I dislike foreigners trying to analyze the US, or foreigners trying to analyze any country, really. You can write about that country, but once you start to analyze it as a foreigner, it becomes much harder, and too often foreigners get things wrong that defeats their premise. As you noted, it’s hard to do, and Ennis certainly doesn’t succeed all that well.

He does thread the needle pretty well in Preacher!