“Some dance to remember, some dance to forget”

Julian Hanshaw creates some interesting graphic novels, and his latest, Cloud Hotel, is one such comic. It’s published by Top Shelf (perhaps not surprisingly, as they’re at the forefront of the “mainstream avant-garde” that Hanshaw represents) and it costs a mere $20.  Perhaps you might want to check it out?

Perhaps you might want to check it out?

Cloud Hotel is semi-autobiographical, at least I hope it’s only “semi-,” because if it’s not, Hanshaw has lived a far weirder life than any of us. He writes at the beginning that the story was inspired by a strange event he experienced with his family in 1980, when a rectangular object hovered over their car and shone a light down on them. They all got out to look at it, then it flew upwards and out of sight. Not the sort of thing you usually see on the A41 to Tring, but okey-dokey. Hanshaw sets the story in 1981, about six months later, and he calls himself Remco (even though we know the character’s real name is “Julian”), but again, I can’t imagine what happens to “Remco” in this comic happened to Hanshaw. Maybe it did.

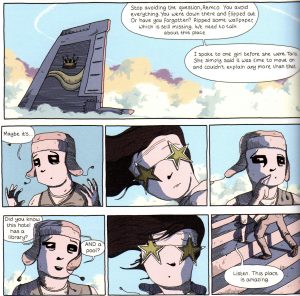

Remco is biking through the forest with his friend Luc at the beginning of the book, looking for the thing he saw in October. He finds it and apparently gets taken into it, but it turns out to be a hotel floating in the clouds. There are two other children there, but one of them doesn’t hang around for very long. Apparently a phone often rings in the hotel, and if it’s for you (you know in your gut that it’s for you), you answer it and leave the hotel, but no one knows where you go. Emma, the other child at the hotel, has been there a long time and has never heard the phone ring, and Remco, apparently, can ignore the phone and come and go as he pleases. He does this early in the book, which mystifies the other children (and then only Emma, as she’s the only one left). We’re never quite sure if the hotel is real or not – Emma, as it turns out, is real, so that would mean Remco can’t be imagining it because why would he imagine Emma if she’s an actual person? Remco refers to it as his “happy place,” even though it doesn’t seem particularly cheery, just someplace where he can hide from the world. His grandfather seems to know something about it, but that never goes anywhere. It remains a mystery even at the end.

It doesn’t really matter what the Cloud Hotel is, or whether it’s real or just a metaphor. Hanshaw uses it to tell the story of lost children, whether they’re actually lost (as Emma is) or emotionally lost, as Remco is for most of the book (he’s actually lost the first time he goes to the hotel, which of course freaks his parents out).  His grandfather, who actually finds him when he gets lost, has a heart attack, which eventually kills him, and his parents seem adrift for most of the book. Remco keeps going back to the Cloud Hotel, not because it’s safe (it most assuredly isn’t, although it’s not actively trying to hurt him), but because it’s a place where he feels more in control. He has a mission – saving Emma, even though he’s not sure how to do that. In his real life, he’s dealing with a death in the family and parents who don’t seem to know how to process that, so how can they help him?, possible alopecia (Remco doesn’t have any hair anywhere, but he never says what causes it), and the bullying that comes from being strange, both with his lack of hair and the fact that he went missing and doesn’t seem quite anchored to reality anymore. There’s also the idea of the hotel offering freedom, as Remco slowly grows up – his parents, again, are scared to let him bicycle through the forest where he disappeared, but at the same time, they recognize that they can’t keep him safe forever. In the hotel, he decides if he wants to answer the phone or not, and he even decides when he comes and goes, and he can work with Emma to figure out what they’re going to do about her. In the “real world,” he can’t save his grandfather, he can’t fix his parents, and he can’t stop the bullying. The nice thing about the book is that Hanshaw doesn’t go out of his way to make this explicit; it’s just part of Remco’s existence. It doesn’t matter if the hotel is real or not, because to Remco, it is, but even so, he realizes that there’s a time to escape and a time to face your reality. Yes, this is a coming-of-age story. I assumed so when it starred a kid who’s obviously a young teen, so it’s a coming-of-age story and a semi-autobiographical story. Yuck, right? Well, Hanshaw is good enough to add some surrealism to everything, and he doesn’t give Remco or any other character easy answers, so those aspects of the comic are tempered, and it means that I can deal with it. Aren’t you glad?

His grandfather, who actually finds him when he gets lost, has a heart attack, which eventually kills him, and his parents seem adrift for most of the book. Remco keeps going back to the Cloud Hotel, not because it’s safe (it most assuredly isn’t, although it’s not actively trying to hurt him), but because it’s a place where he feels more in control. He has a mission – saving Emma, even though he’s not sure how to do that. In his real life, he’s dealing with a death in the family and parents who don’t seem to know how to process that, so how can they help him?, possible alopecia (Remco doesn’t have any hair anywhere, but he never says what causes it), and the bullying that comes from being strange, both with his lack of hair and the fact that he went missing and doesn’t seem quite anchored to reality anymore. There’s also the idea of the hotel offering freedom, as Remco slowly grows up – his parents, again, are scared to let him bicycle through the forest where he disappeared, but at the same time, they recognize that they can’t keep him safe forever. In the hotel, he decides if he wants to answer the phone or not, and he even decides when he comes and goes, and he can work with Emma to figure out what they’re going to do about her. In the “real world,” he can’t save his grandfather, he can’t fix his parents, and he can’t stop the bullying. The nice thing about the book is that Hanshaw doesn’t go out of his way to make this explicit; it’s just part of Remco’s existence. It doesn’t matter if the hotel is real or not, because to Remco, it is, but even so, he realizes that there’s a time to escape and a time to face your reality. Yes, this is a coming-of-age story. I assumed so when it starred a kid who’s obviously a young teen, so it’s a coming-of-age story and a semi-autobiographical story. Yuck, right? Well, Hanshaw is good enough to add some surrealism to everything, and he doesn’t give Remco or any other character easy answers, so those aspects of the comic are tempered, and it means that I can deal with it. Aren’t you glad?

Hanshaw’s idiosyncratic art makes the story odder, too, as his hotel is a bizarre place, despite the comforts of an upscale residence. Hanshaw makes its angles just a bit off and its walls just a bit seedy, so that it looks like a relic from an earlier age, a place that was once grand but has fallen on hard times.  He does a good job contrasting it with the mundane “real world” and the real world’s eerie fluorescent glow – Hanshaw’s colors on the book are superb – as Remco spends too much time in the hospital and other soul-crushing places, making the hotel, despite its ramshackle nature, at least a place with some personality. He does some gorgeous work with fine lines when Remco looks in the books in the library, which represents a person’s life, and his deft and delicate touch is also in evidence when Remco meets his grandfather for the last time, because facial expressions are not applicable (I don’t want to spoil why) and therefore Hanshaw’s work with body language is paramount. He does terrific work with sound effects, not only words but noises, making them almost tangible things, almost attacking the characters at times. You’ll have to get used to the characters’ eyes, which are large black squares with small slits in them, but once you do, they become very expressive even in their simplicity. Hanshaw’s art is strange, but hauntingly beautiful, and that’s the case here.

He does a good job contrasting it with the mundane “real world” and the real world’s eerie fluorescent glow – Hanshaw’s colors on the book are superb – as Remco spends too much time in the hospital and other soul-crushing places, making the hotel, despite its ramshackle nature, at least a place with some personality. He does some gorgeous work with fine lines when Remco looks in the books in the library, which represents a person’s life, and his deft and delicate touch is also in evidence when Remco meets his grandfather for the last time, because facial expressions are not applicable (I don’t want to spoil why) and therefore Hanshaw’s work with body language is paramount. He does terrific work with sound effects, not only words but noises, making them almost tangible things, almost attacking the characters at times. You’ll have to get used to the characters’ eyes, which are large black squares with small slits in them, but once you do, they become very expressive even in their simplicity. Hanshaw’s art is strange, but hauntingly beautiful, and that’s the case here.

Obviously, this is a book that takes some thought once you get into it, because Hanshaw is more about impressions than explication, but it rewards you, too, which is nice. It’s a meditation on loss, growing up, loneliness, strength, desperation, and hope, and its languid pace provides a fascinating contrast to those strong themes, as we get caught up in the strangeness of the hotel before Hanshaw reminds us of the all-too-real consequences of life. Hanshaw remains a very interesting creator, and this is definitely worth a look. And if you are interested, there’s a link down below!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆

Kudos, Greg Burgas, for the recent one off reviews of legitimate ‘non-mainstream’ comics by the lesser known talents. Keep it up.

Thanks, Louis. I try to be eclectic! I wish I had more time to write these reviews, though – I wanted to publish them on consecutive days for as long as they lasted, and it took me more months than I’d like to admit to get enough to make it worth while.

It’s not about “being eclectic”. It’s about showing what else comics has to offer. If you’re going to argue we’re in this ‘new Golden Age of Comics’, then this is the stuff you have to present to prove the true diversity of the medium.

Well, the surface story is about aliens testing children in their version of a “Skinner box”. It seems to double as an allegory for the escapist or autistic behavior of retreating into a “happy place”, the crumbling hotel implying how such short-term alienation leads to long-term deterioration. (A “lesson” kids may not parse and adults may not find enlightening.)

It’s also about childhood’s end. Remco flees his gramp asking him to become a murderer. He doesn’t want to answer the call of adulthood. He rips a piece of wallpaper to stay incomplete and immature. “Remco” doesn’t want to be Julian but will have to.

Emma is an extrovert, always waiting for the phone (hoping to connect with people who find her weird). Remco is an introvert, never answering the phone (scared to get involved with the few people reaching out). They’re both kinda sad and alone until finding each other. (Another nice “lesson” likely to underwhelm kids and unfaze adults.)

Problem is, its layering ala Álvaro Ortiz seems to require an adult active reader to deliver wisdom for teens. Aren’t most kids likely to find it a little slow and baffling, and most adults a little simple for its bafflement? (For similar morals, Scott Mills’s BIG CLAY POT or Kurt Wolfgang’s WHERE HATS GO were charmingly more direct all-ages stories.)

It started as a children’s book and was apparently upgraded to all-ages, ending up kinda neither-fish-nor-fowl. Let’s hope Hanshaw’s next effort will have a better focus on a single audience, like his TIM GINGER?