For me, the best kind of film reference book is one that makes me see movies with fresh eyes. Even movies that weren’t covered in the book.

For me, the best kind of film reference book is one that makes me see movies with fresh eyes. Even movies that weren’t covered in the book.

For example, Heather Greene’s Bell, Book and Camera: A Critical History of Witches in Film and Television, mentions that in contemporary films, the New Age/occult bookstore owner has replaced the old wise woman in the hills as a source of magical advice. Ever since I read it, I keep seeing that cliché pop up, everywhere from The Howling (Dick Miller provides Dee Wallace with the lowdown on werewolves) to the second season of the Charmed reboot.

I had a similar reaction several years ago to Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies by Martin F. Noden. After I read it, it became impossible not to see disability cliches in multiple movies, and also quite frequently in comics.

For example, Nodens discusses the cliché that disabled people “know” they aren’t worthy of accepting love from an abled individual. It wouldn’t be fair to shackle the one they love to a — a cripple! Stan Lee loooooved this one, using and resuing it throughout the Silver Age. The first case I’m aware of is Journey Into Mystery #87: Don Blake wishes he could tell Jane he loves her but he knows “she might pity a weakling like me … but she could never love me!”

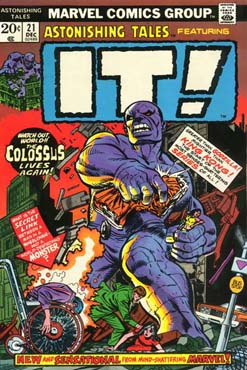

Before too long, it was Professor Xavier’s turn. In X-Men #3, he thinks about how much he loves Jean, but he can’t speak the  words in his heart, not when he’s confined to a wheelchair! Matt Murdock had similar worries about Karen Page. In 1973, when Marvel tried replicating the early Silver Age style and tone with It! The Living Colossus, they unfortunately threw in that same angst. The hero ends up in a wheelchair which convinces him he should break up with his girlfriend. She deserves better!

words in his heart, not when he’s confined to a wheelchair! Matt Murdock had similar worries about Karen Page. In 1973, when Marvel tried replicating the early Silver Age style and tone with It! The Living Colossus, they unfortunately threw in that same angst. The hero ends up in a wheelchair which convinces him he should break up with his girlfriend. She deserves better!

Some of this may be writers transferring their own assumptions about abled/disabled relationships to their characters. Other times it may be reaching for a convenient source of keep-the-lovers-apart drama and not realizing this gimmick has, as they say, problematic aspects. Sometimes it’s just really bad writing like an X-Men story (I think by Roy Thomas but I can’t find the link I had to it) where the team goes off for fun and Professor X rages against his fate — he’s trapped, trapped inside his mansion and alone! Dude, you’re in a wheelchair, not an iron lung!

Another cliché in Nodens’ list is that the disabled in fiction are often isolated. In the real world they form support groups, clubs, murder-ball teams and such; in fiction they’re often outcast freaks. Matt Murdock seemed to be the only blind man in New York during the Silver Age. Nor did Professor X ever hang out with his fellow paraplegics.

That’s one of the things I love about New Teen Titans #8. A kid runs into Cyborg, who fully expects him to freak out. The kid has an artificial arm himself, though, and is quite impressed with Victor’s shiny metal prosthetics. He invites the Titan to play ball and Victor realizes he’s not alone.

While Stan Lee made huge use of disability tropes, DC certainly did its share. The Captain Ahab stereotype — “I have been disabled,  someone must pay!” — defines Jim Shooter’s Tharok, a cyborg angry at the galaxy for becoming a half-human, half-machine (to say nothing of Shooter’s Tarik the Mute, pissed-off because a police blast burned out his vocal chords). Pretty much every scarfaced villain in comics fits this template.

someone must pay!” — defines Jim Shooter’s Tharok, a cyborg angry at the galaxy for becoming a half-human, half-machine (to say nothing of Shooter’s Tarik the Mute, pissed-off because a police blast burned out his vocal chords). Pretty much every scarfaced villain in comics fits this template.

There’s also the cliche of the Exceptional Disabled Person. Wonder Woman’s martial-arts mentor I Ching, for example, is blind but he’s so amazingly good he doesn’t need silly things like working eyes. Why, he’s so much better than his sighted adversaries, his blindness isn’t a handicap! Some people put Daredevil in this category, but as I Ching doesn’t have superhuman senses, he’s a more blatant example.

Over at Marvel, Alicia Masters falls into this category. She’s blind, but in one Fantastic Four story her hearing’s so sharp she’s able to detect Sue by her heartbeat. When she meets Ben she sees right past his rocky exterior to the sensitive, thoughtful soul within. She’s half metahuman, half ethereal angel.

Characters such as I Ching embody the myth that disability doesn’t hold paraplegics/blind people/deaf people back — it’s their own failure to triumph over adversity. Wasn’t Beethoven deaf? Wasn’t John Milton blind? The barriers are all in their attitude, not the real world! It’s an argument I’ve seen everywhere from the otherwise entertaining “Case of the Disabled Justice League” —

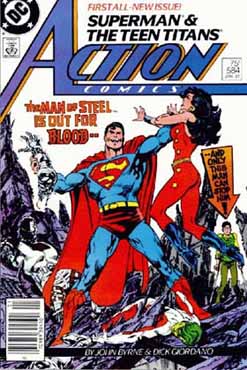

— to one of John Byrne’s early Superman stories, which was not at all entertaining. For double-bonus stereotyping we get a bitter disabled villain stealing Superman’s body, then end with an inspiring lecture about how all the guy needed was the will to overcome his problems.

— to one of John Byrne’s early Superman stories, which was not at all entertaining. For double-bonus stereotyping we get a bitter disabled villain stealing Superman’s body, then end with an inspiring lecture about how all the guy needed was the will to overcome his problems. While I’m not disabled, I’ve read plenty of articles by disabled individuals pointing out this is a big pile of bullshit. Sheer grit and gumption do not make non-ADA buildings any more accessible to wheelchairs. Nor does force of will make it simple for someone with a heart condition or using a walker to hike across a big parking lot because some asshats parked in all the handicapped spaces. Even mental disabilities are not “all in your head” in the sense of being imaginary.

While I’m not disabled, I’ve read plenty of articles by disabled individuals pointing out this is a big pile of bullshit. Sheer grit and gumption do not make non-ADA buildings any more accessible to wheelchairs. Nor does force of will make it simple for someone with a heart condition or using a walker to hike across a big parking lot because some asshats parked in all the handicapped spaces. Even mental disabilities are not “all in your head” in the sense of being imaginary.

As my references to Tharok and Cyborg show, comics can transfer these stereotypes over to cyborgs, mutants and other types of metahumans. In some ways that makes it easier to recycle the clichés: meta-disabilities are so much more extreme than the real world kind, it probably seems perfectly reasonable to have Cyborg or Cyclops (“Cursed by my eyes!” in the words of one Bronze Age story) turn bitter.

That’s not to say every disabled character is a cliche. Birds of Prey got a lot of favorable reviews for its handling of Barbara Gordon (before she got the miracle cure and became Batgirl again, of course). The old New Universe title Nightmask showed the protagonist’s paraplegic sister suffering discrimination. The movie Eternals treats Makkari’s deafness as just a detail, not something that defines her.

Let’s hope the coming years provide more like this and fewer stereotypes.

#SFWApro. Comics covers top to bottom by Gil Kane, George Perez, Jerry Robinson, Mike Sekowsky and John Byrne.

I’ve read the first X-Men epic collection recently, and boy did I get tired really fast. Scott and Prof X made me almost stop reading. I know I’m much older than the target group in the ’60,’s but I wonder how they felt about it.

Well it certainly wasn’t one of their hit books back then; I liked it but I liked almost everything with superheroes. I’ve had other friends who’ve read it in Epic or Masterworks format and they’re not enthused either.

I think it improved considerably around the debut of Juggernaut but never to FF levels of quality.

Daredevil may or may not fit into the category you’re talking about, but I think his blind mentor, Stick (introduced by Frank Miller in 1980 or thereabouts), certainly does.

I could never get into Miller’s Daredevil so I only have vague memories of Stick. I suspect you’re right.

Okay, so I decided to ruminate on the article for a few days before making a reply.

I’ve been a comic reader since 1982 and disabled since 1993.

Put simply, the more recent a story that includes disabled characters is the higher a standard to which I hold it. Honestly, with anything older than a decade I tend to just gloss past thoughtless depictions of disability. I think it is important to acknowledge the failings of the past but there are few older stories (in any medium) that don’t fail us in representation (in at least some of its many forms, E.g. disability, race, sexuality, etcetera).

As for the “She could never love me” trope, I do not actually have a problem with it so long as it’s handled well (fully acknowledging that it very rarely is) because it is a legitimate fear that people with disabilities may wrestle with. The thought that a person cannot have/achieve a thing due to their disability is a very real thing that many disabled people have to contend with, it just needs to be addressed with sensitivity and not laziness. As per usual with representation, it is just best tackled by a writer with personal experience or significant input from people who do have that experience.

I agree, representation tends to be poor the further back we go. Obviously given the amount I reread it’s not a deal-breaker but it is annoying.

Good point about the characters feeling insecure. But you’re right, it’s rarely well handled. At least today people are more aware of the importance of getting a beta read from someone who has lived experience (which is not to say everyone does it).