[Here’s the original post — only one real comment (MarkAndrew’s response to it is brief), but it’s pretty excellent. Enjoy!]

So here we are, moving on to the second issues of the second wave of mini-series. Who wants me to shut up about this epic? Ha-ha, too bad — I’m on a holy mission!!!!

Lots of SPOILERS in this issue, although not much of consequence happens. Again, we’re looking at the weakest of the mini-series, so it’s not surprising that not much happens. But if something does, I will be there to SPOIL it!

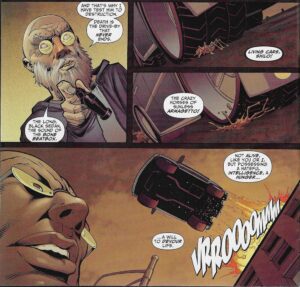

Remember last issue? Shilo Norman was about to face the menace of the Drive-By Derby? Well, hang onto your hats, because here it comes! The old guy in the wheelchair, who sort of revealed last issue that he was Death, the Black Racer (the guy on skis), is talking to Shilo as the cars come at him. He tells him, “From the moment you’re born, you start running,” and this becomes quite literal as Shilo flees from the cars and the eerie figure on skis above them.  Wait a sec — if the guy in the wheelchair is the Black Racer, then who’s the guy on skis? I’m so very perplexed. Anyway, another guy in a wheelchair shows up and reveals that he is actually Metron, whom Shilo met last issue as well. Shilo doesn’t recognize him, but Metron says that it “had to happen this way,” because they need to prepare him for his first experience with “dark side.” The two dudes in chairs face off, and Shilo becomes a pawn in their game of chess — again, literally. Metron holds up a knight and says, “I move palm inductors … white supermagnetic force to black gravity. Power repulse and check.” Shilo gets discs that enable him to levitate over one of the cars. The Black Racer is telling Metron that there are some things no one can run away from, and even the New Gods knew that all things are temporary. Metron says that Shilo will prevail, which is why he was selected, “long ago, in the far future, before the fall.” I’m not entirely sure what this sentence means. Shilo Norman is not a new character, so does this tie into his origin in another book? The reference to the “far future” recalls the Sheeda, who are also from the far future. This is the first reference in the book to the bigger saga, but I’m not certain what it means. “Before the fall” has plenty of Biblical weight to it, of course — the fall of Lucifer, the fall of man — and when Metron says it here, is he referring to the fall of New Genesis? How has time become twisted from what Shilo saw in his vision of the destruction of New Genesis, which seemed to take place in the past? Is time in this series like the actual Möbius strip, which has only one side? And the fact that Metron no longer looks like Metron – and the rest of the New Gods look different — makes me wonder exactly where this series — or at least this part of the series — is taking place. Remember, Shilo did fall into a black hole. Where the heck is he?

Wait a sec — if the guy in the wheelchair is the Black Racer, then who’s the guy on skis? I’m so very perplexed. Anyway, another guy in a wheelchair shows up and reveals that he is actually Metron, whom Shilo met last issue as well. Shilo doesn’t recognize him, but Metron says that it “had to happen this way,” because they need to prepare him for his first experience with “dark side.” The two dudes in chairs face off, and Shilo becomes a pawn in their game of chess — again, literally. Metron holds up a knight and says, “I move palm inductors … white supermagnetic force to black gravity. Power repulse and check.” Shilo gets discs that enable him to levitate over one of the cars. The Black Racer is telling Metron that there are some things no one can run away from, and even the New Gods knew that all things are temporary. Metron says that Shilo will prevail, which is why he was selected, “long ago, in the far future, before the fall.” I’m not entirely sure what this sentence means. Shilo Norman is not a new character, so does this tie into his origin in another book? The reference to the “far future” recalls the Sheeda, who are also from the far future. This is the first reference in the book to the bigger saga, but I’m not certain what it means. “Before the fall” has plenty of Biblical weight to it, of course — the fall of Lucifer, the fall of man — and when Metron says it here, is he referring to the fall of New Genesis? How has time become twisted from what Shilo saw in his vision of the destruction of New Genesis, which seemed to take place in the past? Is time in this series like the actual Möbius strip, which has only one side? And the fact that Metron no longer looks like Metron – and the rest of the New Gods look different — makes me wonder exactly where this series — or at least this part of the series — is taking place. Remember, Shilo did fall into a black hole. Where the heck is he?  (Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about the connections to the other series, which implies it’s in the good old DCU. We’ll get to that.)

(Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about the connections to the other series, which implies it’s in the good old DCU. We’ll get to that.)

The Black Racer tells Shilo that he is being pursued by “living cars,” the “crazy horses of sunless Armagetto!” Armagetto (which is spelled with an “h” after the “g” wherever else I find it) is the main city of Apokolips, Darkseid’s planet, and of course merges Armageddon, the battle at the end of the world, with “ghetto,” so it’s a handy word. Shilo manages to escape into the sewers, and Metron says that he believes Shilo can “restore the gods to their thrones on New Genesis.” Again, we’re left wondering exactly where they are right now. The Black Racer says that Shilo has a mother box, “the last of her kind,” and it would be helpful if “Dark Side” doesn’t get his hands on it. I am left wondering where the other mother boxes are. Are they in a universe that doesn’t have mother boxes, or is the actual DCU now bereft of them? As usual, Morrison makes my head hurt.

Shilo gets in touch with ZZ and tells him to bring a Hummer for him, and he climbs out onto the street as the cops and firemen clean up. He sees the crazy old man in the wheelchair, but can’t catch up to him. He does bump into Metron, who appears to be far more handicapped now than he was a few pages before. Shilo remembers that Metron said they’d meet at the crossroads, which is where they are now. Before he can say anything else, a huge elderly black man accosts him and tells him to take his hands off the chair. Shilo tries to explain, but the man is having none of it. Then he calls the guy in the chair “Metron,” so Shilo follows him and tries to get him to talk, finally blurting out that he has “motherboxxx,” which gets the guy’s attention. The guy takes him back to the “barracks,” which is just a construction site, and shows him all the “troops” gathered there, who are really New Gods. Shilo can see their true selves when he uses his mother box. The big guy who was taking care of Metron is Orion, Darkseid’s son. For the others, check out the annotations. Unfortunately, when Shilo takes out mother box, a sinister Mercedes in the shadows turns on its headlights, and the homeless bunch freaks out and runs for it (this is not unlike when Vincenzo used the cauldron and alerted the Sheeda to his presence). Shilo follows Orion and Metron, and Orion says that they can’t stay there or he’ll see them. Metron says, “Daaaassssyyyy Dakkseddd,” which is probably “Darkseid” repeated twice. A wrecking ball swings in and destroys the squat, and “Dark Side” watches from the car and grins evilly. He does everything evilly, because he’s Darkseid.  The old bearded man, who is actually Highfather, tells Shilo to leave them alone, because they can’t help him. Shilo tries to persist, but Orion shoves him away and they disappear into the night.

The old bearded man, who is actually Highfather, tells Shilo to leave them alone, because they can’t help him. Shilo tries to persist, but Orion shoves him away and they disappear into the night.

We zip back to Shilo’s psychiatrist’s office, where Shilo is talking about the experience. He says, significantly, “Down in the dirt there was brotherhood and community and a vision … like human life, all human life, was so precious … and every individual human story was worthy of … I don’t know … mythology.” I’m not sure how he got that from his brief encounter with the New Gods, but it’s an interesting statement. We have seen sentiments like this before — from Ed Stargard, who believed in giving every person a voice to tell their story. Morrison is showing us that the stuff of fiction, and even of legend, comes from the mundane, if only we have the will to overcome the obstacles in the way. Shilo mentions “mythology” — again, the saga is concerned with what makes a myth a myth, and here it’s implied that we all become myths if the circumstances are right. The “fall” of the New Gods from deities to homeless people doesn’t take away their basic dignity, and Shilo is seeing that his life might be a bit meaningless, despite his success. This is the first step he has to take on his road to transformation. The doctor is unsympathetic, and tries to get him out of the office (saying they’re “going in circles,” another reference to a Möbius strip). He says that Shilo originally came to see him because his rapid rise to fame led to fears that he would lose it just as quickly. Now, he’s had a “quasi-religious confrontation with the existential abyss of meaninglessness.” He says Shilo found a purpose in a life that had none, and every bum on the street has become a divine prophet. The doctor, who is Darkseid’s master torturer Desaad, is playing the role of the Terrible Time Tailor or Melmoth — he is the adult, trying to crush the dreams of the hero. Shilo believes in something — whether or not he’s crazy isn’t the issue — and his belief is helping him look for something more to life. Dr. Dezard is trying to deconstruct that belief and, in the process, destroy it. Shilo mentions motherboxxx, which is just a “toy … somebody made” for him. We can assume it was the Seven Unknown Men who made it, but whether Shilo knows this or not is unclear. Dr. Dezard shows an unhealthy interest in motherboxxx, but Shilo doesn’t want to show it to him. Dr. Dezard lets him go, but tells him he’s worried about his neurological state.  Shilo, don’t ever trust anyone in a Nehru jacket!

Shilo, don’t ever trust anyone in a Nehru jacket!

As Shilo dreams up a new escape, we continue on with Desaad and his machinations. His next client, a Miss Rimbaud, weeps in his office as he talks on the phone. Why Morrison named her that is beyond me, as I know very little about Rimbaud beyond the fact that Leonardo DiCaprio played him in a movie. [Edit: I know Morrison digs Rimbaud, of course, but there doesn’t seem to be a reason to name her that, unless Morrison just wanted to do it and there’s no deeper reason.] Anyway, Desaad is talking to Darkseid, saying that he believes mother box “woke” Metron and is grooming Shilo as a servant of the New Gods. He says he’s been “eroding the boy’s sense of self worth,” but soon the techniques of the healer won’t be enough, and other methods will be needed. Considering Desaad likes the torture, I wonder what he could mean? He pauses to destroy Miss Rimbaud’s fragile ego, and tells her that Dark Side Therapy (people actually go there and think they’ll get better?) can “heal the schism between self delusion and what you truly are.” This reminds us of Uglyhead and how he also showed people what they truly were. Is Morrison saying the artifice is always better? Desaad calls her an “un-person,” which again recalls the insect-like nature of the Sheeda, and he grins as she accepts the “anti-life equation,” which will cause her to “never dream again” nor “love again.” On the other line, Dark Side tells him he’ll take over now. Desaad’s treatment of Miss Rimbaud reveals his plans — Morrison is tying the grand quest of the Fourth World — Darkseid’s lust for the anti-life equation — into the epic of the Sheeda. Miss Rimbaud, like the teenagers in Frankenstein #1, like the Newsboy Army when confronted by the Terrible Time Tailor, like the Puritans when Klarion returns, like Zatanna at the beginning of her series, like Jake Jordan … phew! Where was I? Oh, yes — Miss Rimbaud has been deconstructed, and in doing so, Desaad has made her “grow up.” She no longer believes that she is an artist, because she is so very bad at it. Desaad has made her understand that, and she has become “whole.” But this wholeness is an awful fate, because she no longer dreams. That is what the Sheeda are planning to do — take away mankind’s dreams, because what is civilization but the dream of a better life?

This issue is far more interesting than the first one, which had the better art. Patton and Williams are not quite up to the task, and Dave McCaig’s colors are full of browns and blacks and make everything far too dull.  However, after we get past the silliness of living cars trying to smash Shilo, the themes that Morrison is exploring in this issue tie in nicely with the bigger epic and also show some nice subtleties. The idea of the New Gods becoming homeless “bums” is nice, as it allows them to gain some much-needed humility. One of the biggest problems I’ve always had with the whole Fourth World thing is that, even more than superheroes, these people are so far removed from us puny humans that we can’t relate to them. Even when Forager got killed in Cosmic Odyssey, I was largely unmoved. What Morrison does here, in just a few pages, is humanize them immensely, so that even though they are unheroic, they are still people. They have been beaten down by a far more powerful opponent, and want just to be left alone. No, it’s not what “gods” would do. But it is what people would do, and Metron, at least, is still trying.

However, after we get past the silliness of living cars trying to smash Shilo, the themes that Morrison is exploring in this issue tie in nicely with the bigger epic and also show some nice subtleties. The idea of the New Gods becoming homeless “bums” is nice, as it allows them to gain some much-needed humility. One of the biggest problems I’ve always had with the whole Fourth World thing is that, even more than superheroes, these people are so far removed from us puny humans that we can’t relate to them. Even when Forager got killed in Cosmic Odyssey, I was largely unmoved. What Morrison does here, in just a few pages, is humanize them immensely, so that even though they are unheroic, they are still people. They have been beaten down by a far more powerful opponent, and want just to be left alone. No, it’s not what “gods” would do. But it is what people would do, and Metron, at least, is still trying.

Of course, the major theme of the issue is that the New Gods have lost their dreams, just like Miss Rimbaud. They have been reduced to “normal” people, who simply exist without really living. Morrison has tapped this vein before — I can’t help but be reminded of Crazy Jane in Doom Patrol #63, who never painted again after the psychiatrists were done with her. This idea of fanciful dreams becoming dreary nightmares of reality is nothing new in fiction, of course — I could rattle off plenty of examples, but won’t — and it’s all in how it’s presented. Morrison is doing a fine job showing us various ways the “real world” beats us down. We know the theme is going to come up, but it’s interesting to see how it will be done. Uglyhead brings us the dark side — so to speak — of peer pressure. The Terrible Time Tailor forces the Newsboy Army to grow up, and Melmoth does the same thing with the Deviants. Gloriana Tenebrae takes what is beautiful — Olwen and Galahad — and corrupts it. Now, Dr. Dezard is breaking down what makes each person unique and calling it “self delusion.” Shilo fears the loss of his fame, which is why he is not yet a fully actualized adult. However, the fact that he is a successful escape artist makes him unique, and Dr. Dezard, ultimately, wants to destroy that part of him. If he can’t escape anymore, then Dark Side will gain control of mother box and win. Each time this theme comes up, it becomes more insidious as the Sheeda get closer to their goal. We start with the Queen’s rather blatant corruption of Olwen. We move on to Melmoth’s kidnapping of Billy Beezer, Zor’s attempts with Zatanna, and the Time Tailor’s destruction of the Newsboy Army.  Uglyhead uses what’s in each teenager to destroy the school, and Dr. Dezard is using psychiatry to destroy Shilo. The enemies of dreams are becoming more subtle, possibly because they realize that the Seven Soldiers are slowly gathering, and they haven’t been able to stop them with frontal assaults. Killing dreams requires a softer touch, and that’s what we’ve been seeing in these latter issues.

Uglyhead uses what’s in each teenager to destroy the school, and Dr. Dezard is using psychiatry to destroy Shilo. The enemies of dreams are becoming more subtle, possibly because they realize that the Seven Soldiers are slowly gathering, and they haven’t been able to stop them with frontal assaults. Killing dreams requires a softer touch, and that’s what we’ve been seeing in these latter issues.

The subtleties of the issue notwithstanding, this is still the “worst” of the mini-series (I put it in quotes because it’s still pretty good), because it feels the most disjointed. Yes, the other series had issues that were devoted solely to one story, so those probably should feel disjointed, and this clearly has a narrative thrust from the first to the second issue, but it feels disjointed partly because of the art, and partly because it feels so divorced from the Sheeda-reality. Even Bulleteer, which after one issue doesn’t seem to have much to do with the rest of the saga, has a few connections. Plus, this relies a lot on your enjoyment of the New Gods, and as I said, I don’t enjoy them. So it feels even more disjointed. As far as what Morrison is trying to do with Shilo’s psyche, I enjoy that, but there still seems to be something missing from this series. As it moves on, we’ll have to see how Morrison rehabilitates it.

If you want annotations, you shall have annotations! Jog has some unkind things to say about the issue, although he does a good job telling us why he’s saying them. Anyone else care to link to other reviews? RAB, are you out there? [Edit: Sadly, he is not. At least not at his blog!]

Next: Alix Harrower finds out more about being a superhero! It’s easy, right?