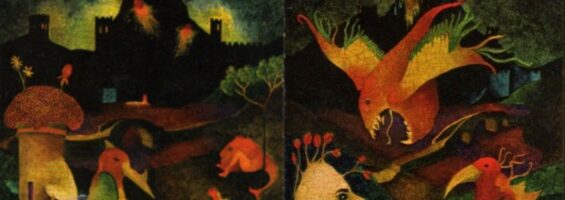

I’m confident everyone reading this blog has seen at least one work of fiction where a great concept was ruined by terrible execution. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land is a perfect example. The execution is very poor. Lin Carter (editor of the Ballantine two-volume reprint with the Robert LoGrippo cover shown below) ranks it as Hodgson’s masterpiece, but I think it’s a poor cousin of The House on the Borderland.

(This is another repost from my own blog)

In the opening scenes, the protagonist (apparently a 1600s or early 1700s guy) meets his dream woman, falls in love, marries, but loses her in childbirth. He’s distraught until he gets a mystical connection with his future reincarnation, living in an era when the sun still provides heat but generates zero light. Covered by endless darkness, the world now swarms with unholy horrors such as the Silent Ones, the Watchers, the House of Silence, the Night Hounds and the Grey Men. The surviving human population huddles inside a gigantic pyramid known as the Last Redoubt, every level of which is a city in itself. Few go outside, and those who do carry the equivalent of a cyanide capsule. If the horrors corner you, you can save your soul at the cost of your life.

The protagonist’s future self, of course, has to go out. It turns out there’s a Lesser Redoubt somewhere in the world and its protective shields are failing. Naani, a woman in the Lesser Redoubt, is in telepathic contact with the protagonist; it turns out she’s his dead wife, reborn into this future landscape as he was. It no longer matters what the risks are or that the location of the Lesser Redoubt is unknown: he’s going to save her or die.

It’s a terrific set-up, and the world outside the pyramids is indeed nightmarish. There are lots of creepy scenes, such as when a band of young men seeking the second pyramid are slowly drawn unawares into the House of Silence and don’t come out. We never learn what’s inside, or what happened to them. Unfortunately, none of the good points make it reasonable.

The first, but not the worst problem, is that Hodgson’s archaic writing style works against him, and against readers (e.g. “While that we were a space off from one of those gas shinings, there went past us at a distance, as it did seem, people running in the night, as that they be lost spirits.”). Even HP Lovecraft, whose style was hardly subtle, thought Hodgson’s style was too affected. When he names the areas around the Last Redoubt, it verges on parody: a headland from which strange things peer is literally named The Headland From Which Strange Things Peer. The road where the Silent Ones walk is named The Road Where the Silent Ones Walk. Sorry, Mr. Hodgson, those are not names. And there are lots more like that.

A bigger problem is Hodgson constantly bogging down the story with mundane detail (I had the same problem with parts of his Boats of the Glen Carrig). Along with describing encounters with giant slugs and Humped Men, the narrator obsessively monitors how long he’s been walking, eating, sleeping —e.g., 12 hours of travel, followed by downing two food pills, six hours of sleep, two more pills, another 12 hours … Maybe Hodgson was trying to ground the story in mundane details, but it didn’t work.

Last but not least, there’s the love story, the emotional core of the book. Love is what keeps the narrator going against all odds; the love story should offer us readers a big emotional payoff too. Instead, it fails on every level. It’s maudlin in the way only Victorians could be maudlin. Hodgson never gives Naani much personality, preferring to describe how utterly, rapturously, sublimely the narrator loves her. I can live with it in the first volume where the hero’s fighting across country to reach her; the maudlin is there but I could skim over it. The second volume devotes way too much space to the hero protecting Naani, gushing about her and cooing at her (as she does to him) and drowns out the horror.

It’s a waste of a wonderful setting.

#SFWApro

volume 1, bottom right corner:

Is one of the Night Horrors Pac-Man?

It’s a vicious circle.

His names are like Friends episode titles.

“The One Where Strange Things Peer From the Headland.” 3rd season. The strange thing turns out to be Gunther from the coffee shop.

I knew it! There was always something a little off about that white-haired young guy.

I still intend to read this some day, so I’ll skip the review for now.

For all its flaws, it’s certainly memorable enough to be worth reading once. Though House on the Borderlands beats it hands down, I think.

As someone with english as second language: That example is hard as hell to read. I got an easier time reading Lovecraft. Shakespeare is really hard too but with Shakespeare at least I got the gist of what he was saying.

As an native English speaker who takes pride in his vocabulistics and ability to read things that are hard to read, I found that line almost illegible too.