[Today, I check out the proper beginning of the SS saga, and while, after re-reading this, I’m more favorably inclined toward the entire thing than I mention here (and in yesterday’s column), I still think this is an excellent issue. Let’s take a look! If you want to read the original comments, you can head over here!]

There is a big problem with Seven Soldiers of Victory #0: it’s too good. It is, in fact, probably the best single issue of the entire Seven Soldiers epic. And that’s not good when it is, in fact, the first issue of the entire Seven Soldiers epic. How does that work? Shouldn’t The God of All Comics have been able to build on what they wrote here and reach greater heights? Ah, but that’s the rub. Today we’ll examine why this is the best issue of the epic, and in later issues we’ll examine why it went downhill (granted, it wasn’t a steep slope, but still). Won’t that be fun?

As I mentioned, SPOILERS abound in these posts. Seriously. Don’t read them unless you know what happens or are prepared to have the ending ruined. BEWARE!

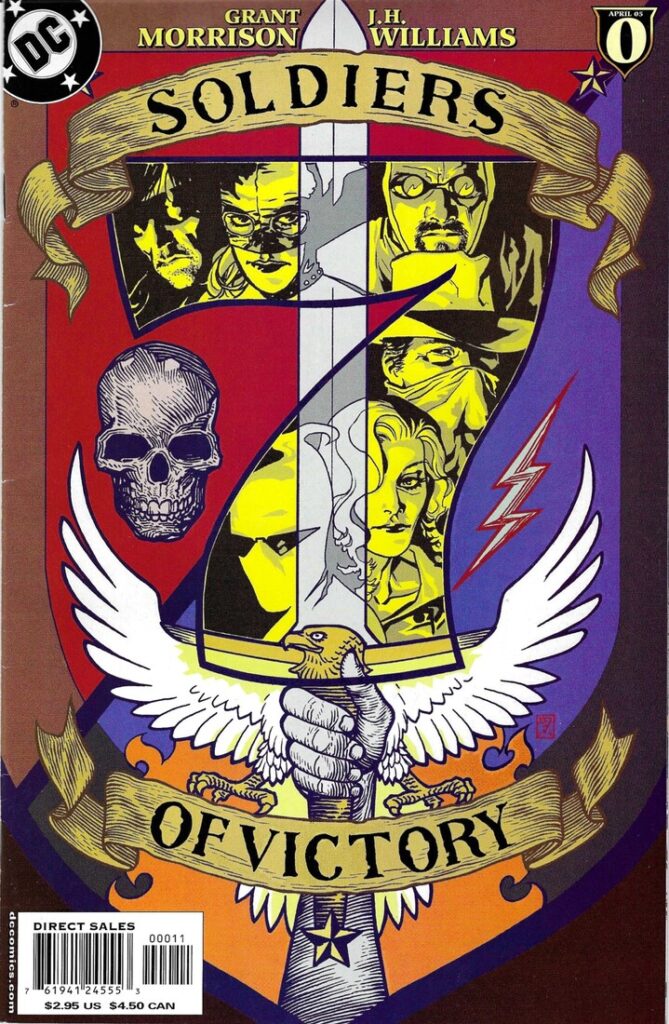

More than JLA: Classified #1-3, Seven Soldiers of Victory #0 is the true prologue to the epic (hence the zero issue number). Morrison introduces all the relevant plot elements, but then pulls the rug out from under us with the shock ending. Now, savvy comics fans would not have been shocked, as none of the characters who star in the seven mini-series that followed this issue actually appear in this issue, but it’s still a bit of a shock ending. In this post I want to look at how Morrison foreshadows the main section of the epic, checking out the themes that they already hashed through less thoroughly in JLA: Classified. Of course, as this is the beginning of the saga proper, there has been a lot more written about it. I will link to the ones I know about below, but have studiously avoided reading the reviews, so I am not tainted by them! I’ll also link to appropriate annotations.

We begin with “True Thomas,” who is being escorted through Slaughter Swamp. The swamp is an integral part of both DC history and Seven Soldiers, and Thomas (a Doubting Thomas, naturally) is unconcerned with the oarman’s contention that “a black flower grows for every secret drowned in Slaughter Swamp.” Slaughter Swamp is familiar for the birthplace of Solomon Grundy, everyone’s favorite gray, mud-spawned thug (although he’s not always a thug, as James Robinson pointed out in Starman). Slaughter Swamp is a “soft place,” a spot where dimensions are easily crossed (a concept first introduced, maybe — unless someone knows differently — in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman). Interestingly enough, it is also the centerpiece of an excellent issue of Swamp Thing, #155, written by Grant Morrison’s protégé (or, perhaps, alter-ego — I mean, have you ever seen them together?), Mark Millar. Both Slaughter Swamp and Thomas will play huge roles in Seven Soldiers, so it’s appropriate we begin with them. It’s interesting to note that in a universe like the DCU, where superheroes and even gods are commonplace, Thomas is skeptical about the legend of Slaughter Swamp. Legends, of course, play a very large role in the epic.

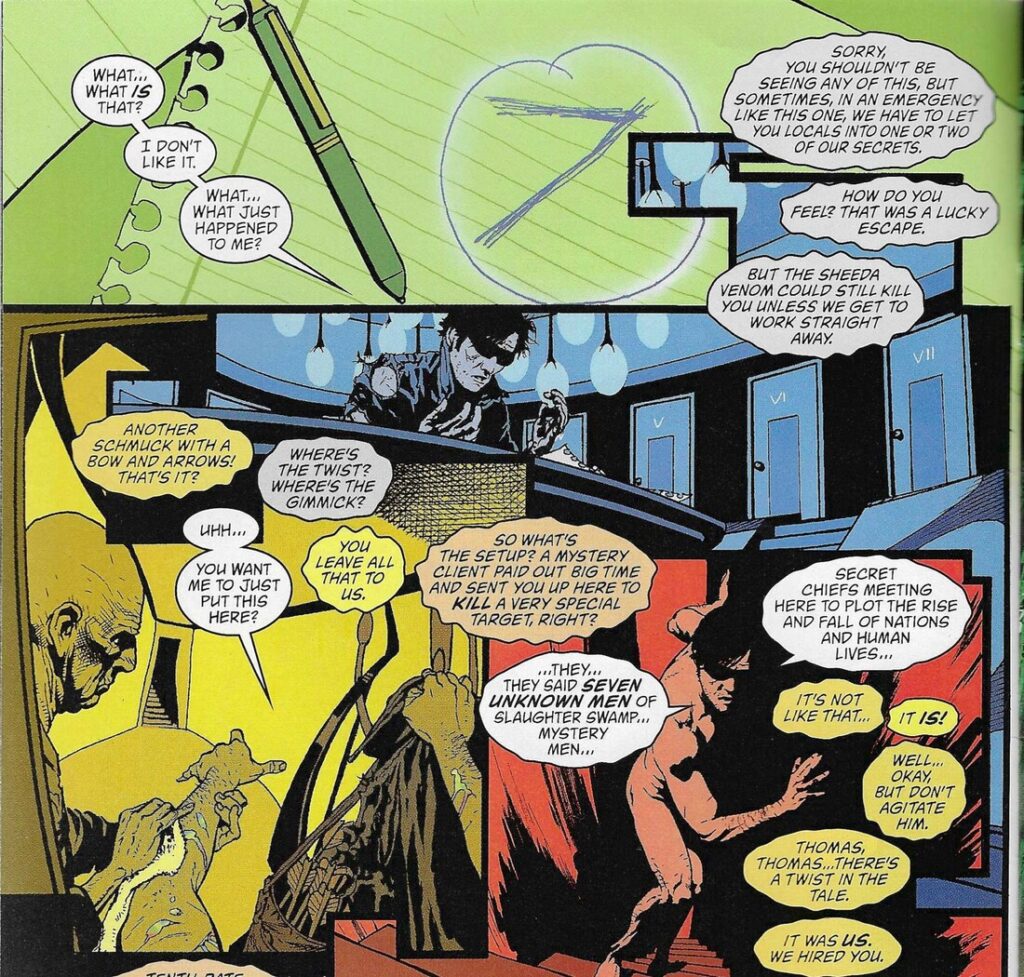

On page 2 (jeez, we’re just on page 2?), Thomas mentions Cyrus Gold, which was Solomon Grundy’s name before he went into the swamp and was transformed. The narrator says significantly (which the only way anyone talks in this saga) that Slaughter Swamp changes things, and can turn “justice and humanity” into monsters. As he says this, a small, armored man riding a mosquito lands on Thomas and bites him. This is a Sheeda rider. Thomas flicks it off as they approach Cyrus Gold’s old shack, which is lit up. We learn that Thomas’ name is Thomas Ludlow Dalt, and his alias is the Spider. Again, given the importance of spiders in the entire epic, should give us some clues as to Thomas’ own importance. Inside, Thomas comes across the Seven Unknown Men of Slaughter Swamp, who hired him to, well, kill himself. Of course, “kill” is meant metaphorically, and Thomas goes into a shower, where he is changed. Somehow. And then the scene shifts.

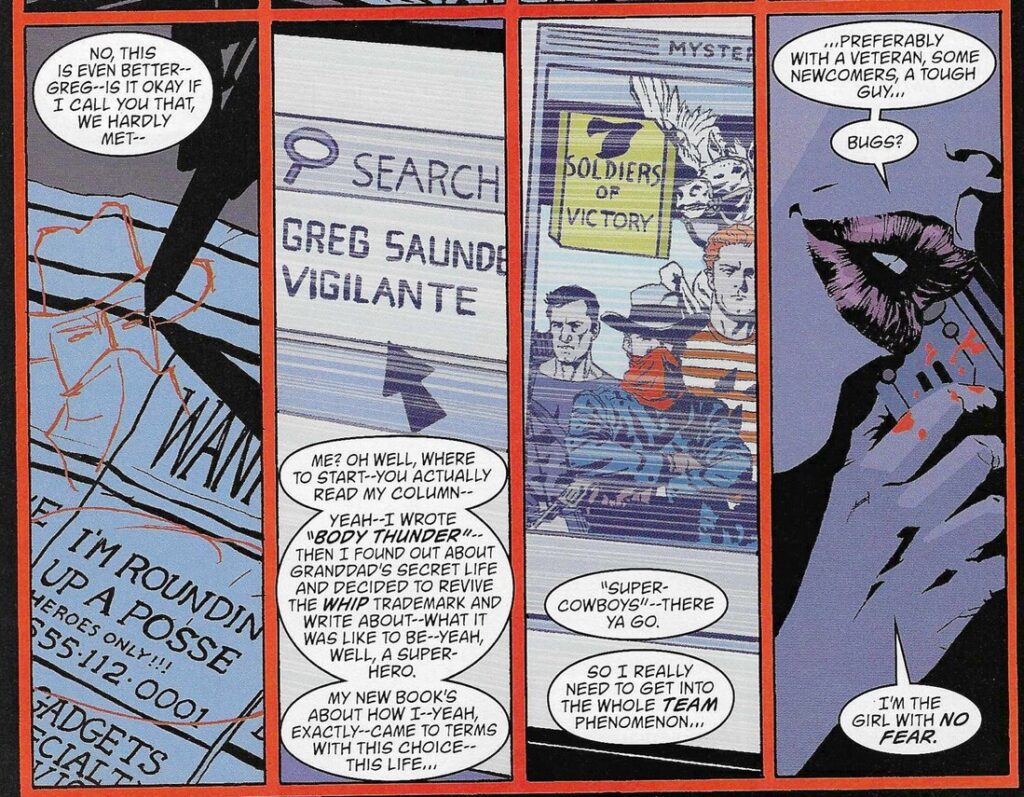

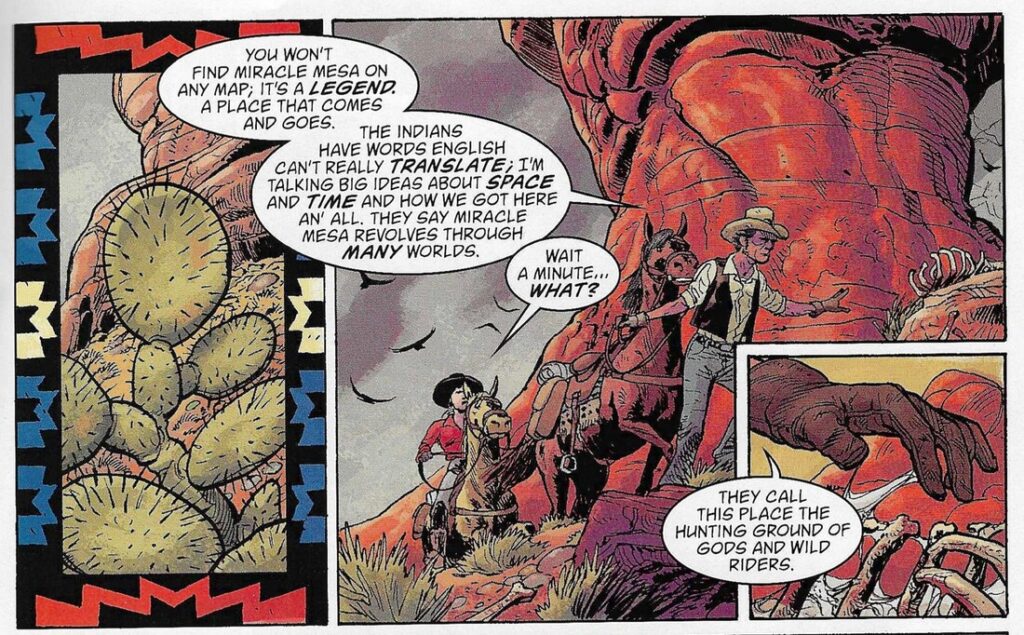

We’re in an ultra-modern city (it’s never identified in this issue, but it’s supposed to be a New York that never was — Morrison and Williams do their homework, apparently), and Shelly Gaynor, aka The Whip, is fighting crime. We find out pretty quickly that she’s a reporter (she’s a writer, too, but she mentions having a column, and later her status as a reporter is confirmed) and she’s also an action junkie, and her grandfather was also the Whip. She answers an ad in the newspaper from Greg Saunders, the Vigilante, who is recruiting a super-posse. She wants to experience being in a super-team, because she’s gone as far solo as she’s going to go. When next we see Shelly, she’s riding through the Arizona desert with Saunders, talking about her grandfather. She asks why he’s putting together a super-posse, and he shows her a newspaper from 12 February, 1875, when he and Johnny Frankenstein fought a giant spider that came out of Miracle Mesa. Miracle Mesa is another “soft place” that “revolves through many worlds” — not unlike Castle Revolving, the headquarters of the Sheeda. Up around Miracle Mesa is the hunting ground of gods. Not a good sign. Shelly asks about the team, and Greg tells her that he wanted to re-create his old team, the Seven Soldiers, but his seventh recruit got cold feet at the last minute. Well, it’s lucky for Alix Harrower that she chickened out, because we find out in Bulleteer #2 that she was the seventh soldier. We meet the team: Gimmix (Jacqueline Pemberton); Boy Blue, who wears a ghost suit that makes him “lighter than air or harder than diamond” and carries a horn that emits sonic impact vibrations; Dyno-mite Dan, who bid for two Golden-Age mystery rings online; and I, Spyder, our old friend Thomas Ludlow Dalt, remade for the mission. Yeah, this can’t go horribly wrong, can it?

In the morning we learn a few things: Jackie Pemberton knows Zatanna from her therapy group, and we see her again in the first issue of that mini-series (which takes place before this issue). Thomas gives us some good, solid information about spiders, and Greg has air scooters to hunt the beast, with video cameras built in. Those will come in handy when other superheroes want to find out what happened to the team. That night, before the hunt, Dan explains the number seven: “There were seven champions of Christendom, seven spirits at the throne of God, seven virtues, seven sins, seven sleepers, seven wise masters … it’s kind of unlucky that there are only six of us, though.” Morrison misses the Seven Chinese Brothers, who are the subject of a new graphic novel published by AiT/Planet Lar and is well worth your money. And what about the Seven Pillars of Islam? And isn’t anyone in this saga a seventh son of a seventh son? I mean, really, Grant! As they find the spider and begin to corral it, Shelly thinks to herself that she’s “all wrapped up in prophecy and myth.” Again, we see a reference to myths and legends. The team works well and kills the spider, but then Boy Blue sees that it’s just a machine. The team hears mission bells (which sounds significant, but I haven’t been able to find out why), which Greg says he last heard in 1875, and they all realize they are the prey. We get a glimpse of Miracle Mesa with (presumably) Castle Revolving above it, and Thomas asks Greg if the Indians called it the hunting ground of the gods, what do gods hunt? The answer is, of course, superheroes. (And Greg told Shelly that, so let’s just assume he told the rest about the hunting grounds of the gods thing off-panel.) We see our old friend Neh-buh-loh mentioning that the harrowing, the harvesting of man, has begun, and then bad things happen. We see Greg, Dan, and Boy Blue die on the page, but we never actually see Jackie, Shelly, and Thomas die. We can assume they die, but with Morrison, you should never assume anything.

The epilogue sets up the rest of the epic. The Seven Unknown Men are justifiably upset by their team’s demise, and we get glimpses of their Plan B. One of them quotes a Welsh Arthurian poem about knights going into Castle Revolving and only seven returning, a snippet that will come up again later in the saga. They drag “gifts” out of boxes — a knight’s tabard, the Guardian’s helmet, and Frankenstein’s rifle are the ones we see — wrap them up, and “leave the time-sewing machine” behind as Sheeda swarm in. There are, significantly, only six men leaving. Where’s the seventh? And, of course, there are six flowers in the swamp. Does it mean that only six heroes died? It could, as I, Spyder survived. Does it mean that there are only Six Unknown Men, not seven? What the hell?

So what does all this folderol mean? Well, let’s look at the transformative theme of the book first. Morrison has always been really big on transformations, and this entire epic is in some way linked to that sort of idea. Thomas is transformed from the Spider into I, Spyder, and in order for this to happen, he must be physically transformed. The Seven Unknown Men of Slaughter Swamp tell him that he’s finally going to get “his starring role in the end of the world drama.” Hints like these are what make reading a Morrison epic so enjoyable. I, Spyder shows up a few times in the mini-series, but as an ally of the Sheeda. This is, presumably, because the Sheeda riding the mosquito in the first few pages stabs him with a venom-tipped spear and infects him. But in the end, he becomes the Seventh Soldier, countering Klarion’s treachery with some of his own. He becomes a substitute Seventh Soldier (a Matthias, perhaps?), restoring the balance. But that’s a topic for another day.

The transformations continue with Shelly Gaynor and the rest of the team. Shelly, as the narrator, gets the most screen time, but her transformation is just as, well, sad as the rest of the team’s. Shelly becomes a superhero to sell books. She tells Greg Saunders that her new book is about how she “came to terms with this choice.” It’s interesting to note that this kind of statement could be made by those kinds of people who don’t like “alternate lifestyles” — Morrison, I’m sure, believes that homosexuality, for instance, is a biological determination and not a “choice,” but it’s interesting to read that statement and wonder about what mainstream America considers “deviant” — how different are fetishists from superheroes? Morrison isn’t interested in exploring that aspect of the book all that much, because it’s been done before (by them, as well as others), but it’s still there, subtextually. [Given that Morrison came out as non-binary, this aspect of the saga can be looked at in a new way, but I’m not doing that here.] Shelly looks at her first book, Body Thunder, which has as its subtitle: “How I Turned My Body Into a Living Weapon to Beat the 21st Century Blues.” It appears that she turned to extreme sports (she’s jumping out of an airplane on the cover) and then superheroing. This is a woman for whom transformation has become a drug, and it’s all she does. Can we really consider another transformation something that brings change when it comes to Shelly? If your natural state is change, what’s one more? The tragedy of Shelly, unlike the tragedies that beset the other team members, is that she doesn’t really exist anymore. The others have transformed themselves once and become something new. But Shelly has transformed so often that there’s nothing left. Yet, her passing is noted more often than the others, despite that fact.

The others, of course, have all gone through their own transformations. Jackie Pemberton has even gotten a facelift. They are all desperate to belong to something, and in the DCU, super-groups take the place of churches, fraternities, Masonic lodges, and knitting circles. They may appear pathetic, but Morrison doesn’t poke fun at them — they realize the human need to belong, and is sympathetic to that. The transformations they have gone through give them the trappings of heroism, but, of course, don’t make them heroes. Greg Saunders remains the rock at the center of the group, streadfastly tracking a monster he last fought 130 years before.

With transformation, of course, comes the notion of heroism that Morrison wants to explore throughout the series. If you’re going to make yourself into a superhero, it would help if you did something heroic. That’s why these people come to Arizona and fight the Miracle Mesa Monster. Morrison makes it clear, however, that it’s far more difficult to be a hero than just dressing like one. The Seven Soldiers don’t do much, as even their triumph over the giant spider is a trap. However, their failure means that the seven replacements’ struggles to become heroes is highlighted — Zatanna is the only one comfortable with being a superhero, but even she needs to learn something. They have to be heroes even though they’re not exactly sure what they’re fighting against — the nature of their mission being that they can’t even know they’re a team. So Morrison shows us heroes as failures so we can appreciate more when the new heroes succeed.

So why is this the best issue of the epic? Well, J. H. Williams III on art certainly helps. Williams is a true artist, changing styles to match the tone of the book, from a futuristic New York to a rough, hard-bitten Arizona desert to an ethereal Slaughter Swamp. He does a wonderful job setting Morrison’s mood. It’s not really the fault of the artists who follow him on the mini-series, but Williams sets such a high standard that we can’t help but be disappointed with what follows.

However, that’s not the only reason. Morrison is very good at setting things up, and that’s what this issue is all about. Yes, it tells a complete story, in that we find out what happens to the six members of Greg Saunders’ team, and that doesn’t hurt, but it also promises a great deal more, information we learn as the mini-series unfold. Morrison, unfortunately, can’t stop throwing bits of information into their work, and when they should be wrapping things up, they’re still being too enigmatic. We appreciate the foreshadowing in this issue, because we know there is a lot to come, but as the end comes closer, we don’t want new mysteries introduced, and in Seven Soldiers #1, as we’ll see, we get a lot of questions to go along with our answers. Knowing that Morrison is allowing DC to run with these characters doesn’t change the fact that this saga ought to have a proper ending, as it has a proper beginning. Beginnings are always full of hope, anyway, and Morrison is one of the best in the business at writing things that make us anticipate greater things. Sometimes they manage to deliver, as well.

So that’s Seven Soldiers #0. It contains a lot of foreshadowing but tells a compelling story. It contains themes that will re-occur time and again throughout the 29 issues that follow it. It’s a marvelously complex piece of comics literature that is also easily understood. No wonder everyone got excited about the epic!

Some other sources: Rich Johnston has some good thoughts on the issue (you have to scroll down); there’s also an annotation up, but surprisingly, it’s not very thorough, which makes me think I might have to do some notes for this issue in the future (but that’s a long way off). Jog and Marc Singer, who are a lot smarter than I am, have their own thoughts as well. If, you know, you’re interested. If anyone else has any good links about this issue, let me know and I’ll edit them in. [UPDATE:] Patrick has some very good thoughts on the issue, as he reminded me in the comments. I saw the link in a previous post and forgot about it. It’s very good. I’d search for them, but there are only 24 hours in a day, which is why I need you guys to point them out! And, of course, feel free to offer your own interpretation of the issue in the comments. That’s why blogs are cool, after all — interaction!

Next: The Shining Knight!

I might trust a Solly…but I’ll never trust a Ludlow!!!

When I first did this, I completely missed that he was a Ludlow. I should have, but I didn’t! I assume Morrison was linking him to Robinson’s Starman, because they would have done something like that, of course!