“Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’, heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin'”

Magnetic Press publishes some cool non-American books, so this time around we get Hard Melody by Lu Ming, which was published in China a few years back (2013, maybe?) and is now available in English.  It’s translated by Jeremy Melloul.

It’s translated by Jeremy Melloul.

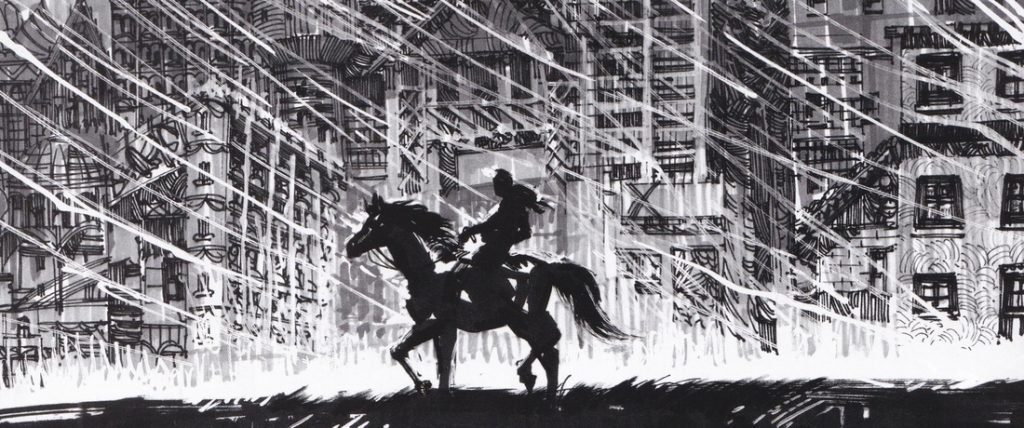

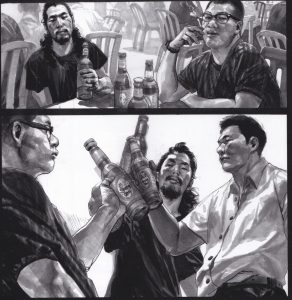

Lu dedicates this to Sergio Toppi, and it’s not surprising, because he’s clearly influenced by Toppi, which isn’t a bad thing at all. His art is terrific, a bit more realistic than Toppi’s, but still scored with beautiful hatching that creates texture from simple multiple parallel lines. He varies his line weight superbly, making the edge of a guitar a bit lighter to indicate its relative delicacy, while characters’ rough clothing is hatched a bit more heavily. A few scenes are set in the steppe-land of Inner Mongolia, and Lu uses gouache and heavy lines to show the power of nature. He doesn’t just ape Toppi, though. Most of the book is gray-washed, not scored in black and white, which aids in the realism. Lu is showing the terror and power of youth at the beginning of the book, so he uses heavier lines and a starker palette, but then he transitions to the safety and complacency of early middle age, and so he uses a softer palette. He uses some digital effects, but he blends them into the narrative very well, so they’re not terribly noticeable. His characters age, but they don’t change too much, with the exception of the drummer, Heizi, who becomes a soldier and has some bad experiences. Lu draws him as a relatively clean-cut dude before the army, but when he comes out, he’s become more stoic and he grows his hair and beard long, standing out even in the more open Chinese world he lives in. Heizi speaks very little, but he has seen bad things in the world, and he’s the one who observes the injustice around him and is willing to do something about it.  Lu does a nice job showing how aware he is, even as his friends are chatting, of what’s going on around him. As Heizi speaks so little, Lu does this with his drawing, and it’s a nice trick.

Lu does a nice job showing how aware he is, even as his friends are chatting, of what’s going on around him. As Heizi speaks so little, Lu does this with his drawing, and it’s a nice trick.

The book begins simply enough, with three dudes playing in their punk band at a festival in 2000. Then we get a few updates over the next few years, as they move on, until 2012, when the three of them are in Beijing at the same time and they get a drink. Naturally talk turns to getting back together, and they do, but Lu doesn’t make the story about that, as an event occurs that kind of throws a spanner in the works. And that’s it.

I’m always worried about reading things in translation, even though I’m sure this is a good one. My problem isn’t with the words, but the cultural baggage someone brings to a story like this. It feels universal, sure – three dudes who didn’t follow their dreams of music stardom are feeling the itch again because their lives aren’t quite what they thought they would be: such is the stuff of a thousand clichéd tales. It’s not that, though, as it feels like I’m missing things that might be more evident to a Chinese audience, simply because Lu is Chinese.  I feel a bit of a disconnect with the characters, and I’m not sure if that’s because Lu doesn’t do the necessary legwork or because I’m missing something in the translation. This is especially the feeling with Heizi, as being a soldier in China seems like a different experience even than being one in the States, but maybe I’m just not getting it. Heizi is deeply troubled, and his actions late in the book seem a bit extreme, even for someone who’s had a hard time in his life. There’s also a fight in the middle of the book that makes no sense, unless we just chalk it up to the universal male desire to be idiotic, in which case it makes perfect sense. The book shifts from a mid-life crisis to something more political very quickly, and this is where I wonder if not being Chinese is blunting the impact of the book. I’m not saying that we don’t have street-level political problems in the States, of course, but the situation in the book escalates really severely, and it feels disjointed. It’s not quite as powerful as Lu wants it to be, because it comes from out of relative nowhere. It’s frustrating. Lu wants to link the world of punk, where people talk (or sing) a good game, with the real world, where actions are needed, but it doesn’t feel like he quite makes it. Still, it’s a fairly powerful ending, just not as strong as I suspect it was supposed to be.

I feel a bit of a disconnect with the characters, and I’m not sure if that’s because Lu doesn’t do the necessary legwork or because I’m missing something in the translation. This is especially the feeling with Heizi, as being a soldier in China seems like a different experience even than being one in the States, but maybe I’m just not getting it. Heizi is deeply troubled, and his actions late in the book seem a bit extreme, even for someone who’s had a hard time in his life. There’s also a fight in the middle of the book that makes no sense, unless we just chalk it up to the universal male desire to be idiotic, in which case it makes perfect sense. The book shifts from a mid-life crisis to something more political very quickly, and this is where I wonder if not being Chinese is blunting the impact of the book. I’m not saying that we don’t have street-level political problems in the States, of course, but the situation in the book escalates really severely, and it feels disjointed. It’s not quite as powerful as Lu wants it to be, because it comes from out of relative nowhere. It’s frustrating. Lu wants to link the world of punk, where people talk (or sing) a good game, with the real world, where actions are needed, but it doesn’t feel like he quite makes it. Still, it’s a fairly powerful ending, just not as strong as I suspect it was supposed to be.

Still, this is a solid comic about people who think the world has passed them by but who figure out that they just need something else to inspire them. It’s a beautiful comic, too, which isn’t nothing. If I don’t love it, it does intrigue me, and Magnetic seems to be committed to bringing more of Lu’s work to the mouth-breathers here in the States, so I’m looking forward to that. So this book got me interested in yet another comics creator, so that’s pretty keen!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆