Let’s journey back to when men were men and everyone looked for treasure with no consequences!

Alvar Mayor by Carlos Trillo (writer), Enrique Breccia (artist), Vladimir Jovanovic (translator), and Dekara (letterer).

Published originally in Argentina between 1977-1983, collected in four volumes by Epicenter Comics, January 2022 – December 2023.

I mean, there’s not much to SPOIL, so still beware, but don’t fret too much! And be sure to click on the scans to giganticize them!

Alvar Mayor looks like a pure adventure story, and while those can be fun to read, they’re not necessarily “Comics You Should Own.” I’ve done some goofy comics in this series, sure, but I would argue that even the goofiest ones I’ve spotlighted have something else, something that elevates them beyond a simple “adventure” story that entertains but is ultimately forgettable.  Alvar Mayor falls into that category, I will argue. Sure, it’s about a dude who wanders around South and Central America in the later 1500s and has all kinds of adventures, but there’s some deeper things going on, too, which make it a classic of the genre.

Alvar Mayor falls into that category, I will argue. Sure, it’s about a dude who wanders around South and Central America in the later 1500s and has all kinds of adventures, but there’s some deeper things going on, too, which make it a classic of the genre.

Carlos Trillo, who was in his 30s when he created the strip (Trillo died in 2011), gives us a dude whose father was in Pizarro’s expedition to conquer the Incas in the 1530s and whose mother, according to the introduction by Danilo Chiomento, was Inca, although we don’t learn much about either parent and the circumstances of Alvar’s birth (his father shows up in one flashback story, but even then, we don’t learn much about him or Alvar’s mother except that they both died tragically). Given the prevalence of rape at this time of native women by Spanish soldiers, perhaps it’s for the best (Alvar’s father is a good dude, but it was still the 1500s, after all). Alvar is a guide whose best friend is an Indian, Tihuo, who comes and goes from the strip almost randomly, as if Trillo remembers him occasionally and thinks, “Oh, dang, I should include Tihuo!” We learn a little bit about both men, but not too much — the strip sticks to Alvar guiding foolish men (and occasionally women) around the Americas, usually looking for treasure. They rarely find it, of course, or if they do, it’s not what they expect.

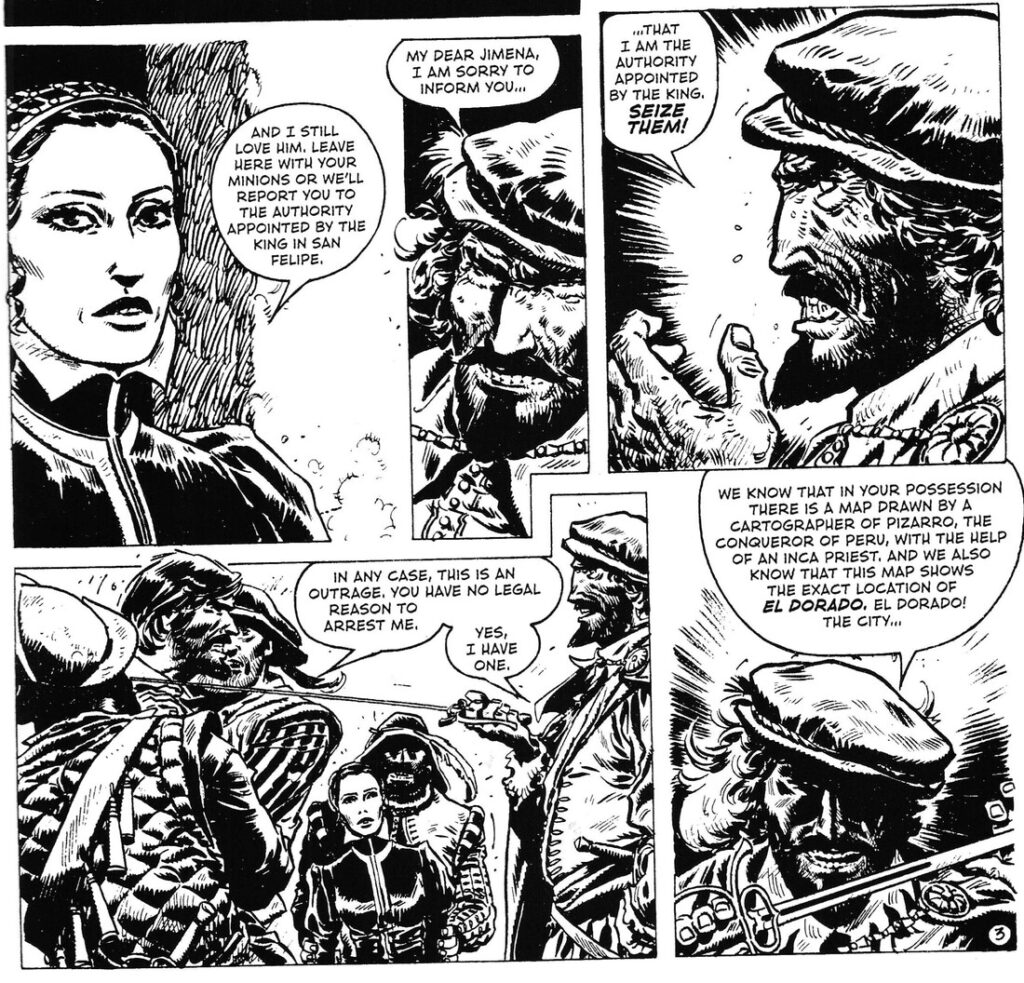

The first story is a good example of the kind of tale Trillo tells. A brutish nobleman enters a random town in South America and breaks into a man’s house, angry that he “stole” his woman from him (she says that she loves Zuniga, but, of course, the nobleman ignores her).  The count claims that Zuniga has a map showing the way to El Dorado and he’s planning on taking all the gold for himself instead of giving a percentage to the Spanish king. He’s lying, of course — Zuniga requested royal permission for the expedition — and Don Felipe kills him, because it’s all about the woman, really. He rapes Jimena, who kills herself that night, and the next day, Alvar Mayor enters the story to ask to be his guide to El Dorado. Alvar isn’t a complete scumbag, though, and he lures Don Felipe into the jungle, where he meets a deserved fate. Alvar wanted the map because it belonged to his father, and he was going to go on an expedition with his very good friend, Zuniga. He and Tihuo leave the count in the jungle.

The count claims that Zuniga has a map showing the way to El Dorado and he’s planning on taking all the gold for himself instead of giving a percentage to the Spanish king. He’s lying, of course — Zuniga requested royal permission for the expedition — and Don Felipe kills him, because it’s all about the woman, really. He rapes Jimena, who kills herself that night, and the next day, Alvar Mayor enters the story to ask to be his guide to El Dorado. Alvar isn’t a complete scumbag, though, and he lures Don Felipe into the jungle, where he meets a deserved fate. Alvar wanted the map because it belonged to his father, and he was going to go on an expedition with his very good friend, Zuniga. He and Tihuo leave the count in the jungle.

Trillo doesn’t deviate from this formula too much, but he does do a lot within it. His women aren’t always ornamental or byproducts of the main action, but, like Tihuo, they’re often an afterthought. When he does want Alvar to interact with a woman on a more serious basis, he does it, but they’re often incidental to the story. Trillo doesn’t seem to trust groups — whether Spanish or native, whenever Alvar encounters a tribe or group, they tend to be antagonistic toward him and his allies. He joins small groups from time to time, and very rarely does it work out well, and if it does, it’s usually the smaller the group, the better. The strips stand on their own, but Trillo does work in some longer arcs — toward the end of the first volume, Alvar gets together with Lucía, who is about to be hanged because the townspeople think she’s a witch. Alvar does what he can to rescue her, but like in a lot of the stories, Trillo doesn’t make him the hero — he acts heroically, but outside forces eventually free him and Lucía. They spend some time searching for treasure, and eventually, they team up with Don Gonzalo Pedrera, who also is looking for treasure.  The first part of the second volume is about the adventures these three have together, forming a short arc that still remains true to the spirit of the strip, as each installment is its own separate story. The adventure doesn’t end happily, and Alvar moves on. Later, he has an adventure with a storyteller, the girl who loves the storyteller, and a group of refugees from an insane asylum, and the stories become more bizarre than ever. Even through that, each section is its own short tale. Trillo doesn’t waver from that.

The first part of the second volume is about the adventures these three have together, forming a short arc that still remains true to the spirit of the strip, as each installment is its own separate story. The adventure doesn’t end happily, and Alvar moves on. Later, he has an adventure with a storyteller, the girl who loves the storyteller, and a group of refugees from an insane asylum, and the stories become more bizarre than ever. Even through that, each section is its own short tale. Trillo doesn’t waver from that.

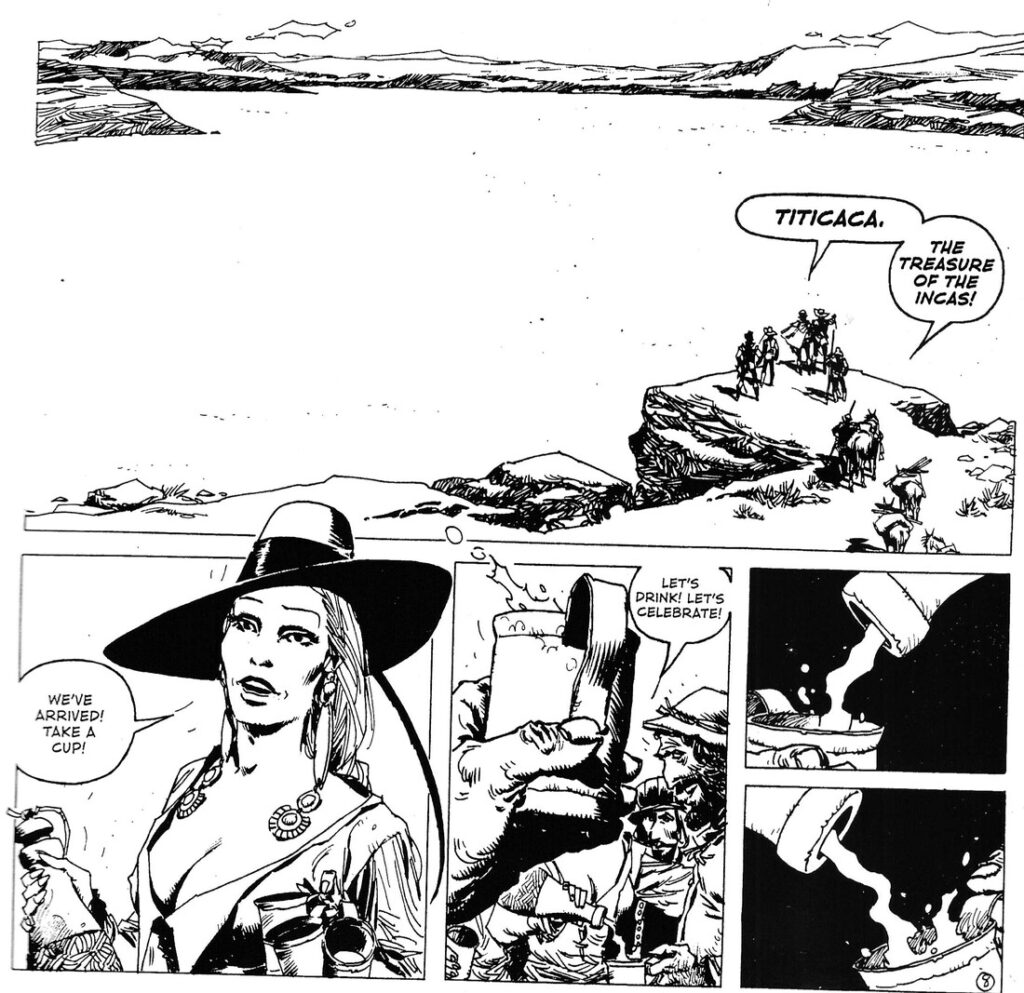

The stories, as I noted, fall into similar themes: people are searching for things, and they hire Alvar to guide them. But early on, Trillo begins to introduce elements of magical realism into the stories, and Alvar Mayor becomes a much more phantasmagorical book than you might expect. As the series begins, we get: the story I noted above, about the haughty nobleman who meets his fate in the jungle; a story about Spaniards enslaving Indians and Alvar and Tihuo’s fight to free them; a man who believes that in Macchu Picchu is the key to immortality but discovers that he’s sorely mistaken; and a story in which Alvar and Tihuo guide two competing groups to Lake Titicaca in a race to see who can reach it first (it is in this story that Alvar bets his magnificent hat and loses to Tihuo, but in the very next story, he has it back, which is indicative of Trillo’s regard for “continuity”). Those are the first four stories, and they’re fairly straightforward. Then, in the fifth story, Alvar meets an older version of himself, who tells him a prophecy about upcoming events which come true perfectly, much to Alvar’s chagrin. After that, Trillo starts to get a bit weird. Alvar fights different gods and spirits; Alvar dreams of Lucía before he ever meets her; Alvar faces off against a Yeti; a troupe of actors that join his adventure with Lucía and Don Gonzalo can predict the future; Alvar meets Homer and fights Polyphemus the Cyclops; Alvar frees cursed lovers who have been transformed into flowers; Alvar has to fight three reflections of himself at different stages in his life that emerge from magic mirrors;  Alvar dreams that he rescues Lucía and other women from slavers, and when he awakes, his dream has come true; Alvar finds himself in a Red Riding Hood story, but with a twist; Tihuo tries to rescue a girl from being a human sacrifice, but she saves herself by turning into a bird; Alvar meets an old man who tells him three ways he will die; a man asks Alvar to guide him to a river that will bring his dead lover back to life … a lover whose corpse he drags around in a coffin; a man sits by a river for twenty years waiting for the corpses of his enemies to float by; Alvar goes on an adventure and meets his doppelgänger. The fascinating thing about these stories is that none of them are strictly fantastical — in every one, it could just be normal, everyday stuff happening, but filtered through the perception of people who want to believe in the supernatural. Some could just be fever dreams, some could be coincidence, and some could just be people lying to Alvar and to themselves. It’s clever, because Trillo wants to show humankind in all its venality and corruption, but he also wants to show how people can overcome great odds, as well. By using this magical realism trope, he can delve deeper into the human condition than he could if all of Alvar’s adventures were more mundane.

Alvar dreams that he rescues Lucía and other women from slavers, and when he awakes, his dream has come true; Alvar finds himself in a Red Riding Hood story, but with a twist; Tihuo tries to rescue a girl from being a human sacrifice, but she saves herself by turning into a bird; Alvar meets an old man who tells him three ways he will die; a man asks Alvar to guide him to a river that will bring his dead lover back to life … a lover whose corpse he drags around in a coffin; a man sits by a river for twenty years waiting for the corpses of his enemies to float by; Alvar goes on an adventure and meets his doppelgänger. The fascinating thing about these stories is that none of them are strictly fantastical — in every one, it could just be normal, everyday stuff happening, but filtered through the perception of people who want to believe in the supernatural. Some could just be fever dreams, some could be coincidence, and some could just be people lying to Alvar and to themselves. It’s clever, because Trillo wants to show humankind in all its venality and corruption, but he also wants to show how people can overcome great odds, as well. By using this magical realism trope, he can delve deeper into the human condition than he could if all of Alvar’s adventures were more mundane.

And despite some of the weirder stories, Trillo is much more interested in examining what makes people tick. The old stand-bys, of course: love (or lust) and money, but writers have been digging into those two plot devices since the invention of storytelling, and there’s always room for more mining! As Alvar is a guide, the money is more prevalent in the strips than love, and Trillo does a nice job showing the folly of lusting after gold too much. He often employs savage irony in these stories, and Alvar is usually there to give a wry, knowing look as the people around him descend into clutching, greedy fools. Of course, Trillo blends greed and lust often, because they go together so well.  There are several examples: when Alvar guides the group to Lake Titicaca, the woman betrays her husband to canoodle a much more handsome man on the expedition, and everyone pays the price for their avarice. Alvar visits an old flame who refuses to see him, and another man, who has lusted after her, kills her father and claims her, which turns out very poorly for him. Two men fighting in a battle argue over one woman, and they both act rashly and dangerously to gain her love … but neither do. Two old men ask Alvar to help them search for the water of immortality, but, of course, they fight each other over it and kill each other. Alvar and Lucía find an old man in the jungle, defending a native temple with the members of his expedition, who are all dead (but whom he propped up to appear as if they’re alive) — he’s gone insane over the years, obviously, and he only wants help uncovering the treasure, which turns out to be worthless. When Lucía leaves Alvar, it’s because she doesn’t believe he can make her rich, and her desire for gold is greater than her love for Alvar. Alvar believes that the search is what’s worth it, while Lucía — and many others in the strip — believe the treasure is the real prize. Trillo is kinder to Lucía than he is to most of the characters, partly because she’s a woman and partly because she does not betray Alvar, simply tells him what she wants.

There are several examples: when Alvar guides the group to Lake Titicaca, the woman betrays her husband to canoodle a much more handsome man on the expedition, and everyone pays the price for their avarice. Alvar visits an old flame who refuses to see him, and another man, who has lusted after her, kills her father and claims her, which turns out very poorly for him. Two men fighting in a battle argue over one woman, and they both act rashly and dangerously to gain her love … but neither do. Two old men ask Alvar to help them search for the water of immortality, but, of course, they fight each other over it and kill each other. Alvar and Lucía find an old man in the jungle, defending a native temple with the members of his expedition, who are all dead (but whom he propped up to appear as if they’re alive) — he’s gone insane over the years, obviously, and he only wants help uncovering the treasure, which turns out to be worthless. When Lucía leaves Alvar, it’s because she doesn’t believe he can make her rich, and her desire for gold is greater than her love for Alvar. Alvar believes that the search is what’s worth it, while Lucía — and many others in the strip — believe the treasure is the real prize. Trillo is kinder to Lucía than he is to most of the characters, partly because she’s a woman and partly because she does not betray Alvar, simply tells him what she wants.

After Lucía leaves him, about halfway through the book, Trillo becomes more esoteric, but the themes remain fairly consistent. A man hires Alvar to find the “last Mayan city,” which he dreamed about, because there’s treasure there. Once he gets there, another character tells him a dream about treasure that takes the man right back to where he started (this story does have a happy ending, which is nice of Trillo). A man hires Alvar to find a woman another man stole from him, but she is not what you might expect.  Soldiers fighting for a lord kidnap Alvar and Tihuo to help fortify the lord’s castle against a coming attack, but the attack is unlike what we think it will be. The man who brings his dead lover back to life finds out that it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. Alvar helps a young wife escape her oafish husband with her dashing lover, and the husband is more sanguine about it than usual, so he gets to live, even if it’s a lonely life. When Alvar goes on his second long adventure (in volume 4), Trillo contrasts the straightforwardness of the insane with the calculating of the sane, and while neither are completely admirable, the insane men highlight the foolishness of the sane quite well, in case we’ve missed it so far.

Soldiers fighting for a lord kidnap Alvar and Tihuo to help fortify the lord’s castle against a coming attack, but the attack is unlike what we think it will be. The man who brings his dead lover back to life finds out that it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. Alvar helps a young wife escape her oafish husband with her dashing lover, and the husband is more sanguine about it than usual, so he gets to live, even if it’s a lonely life. When Alvar goes on his second long adventure (in volume 4), Trillo contrasts the straightforwardness of the insane with the calculating of the sane, and while neither are completely admirable, the insane men highlight the foolishness of the sane quite well, in case we’ve missed it so far.

I’ve written about the basic plots and tried not to give too much away, because the way Trillo shows us these people is very nicely done. The book is populated by a wide array of characters, some noble, some base, some sane, some mad, some attractive, some homely, and all subject to the foibles and failings of humanity, as well as embodying some of the better qualities of people. The men and women (but mostly men) in Alvar Mayor don’t always do the right thing (Alvar, however, always tries and usually succeeds), but they also aren’t pure evil — they’re just people looking for meaning in their lives, and some are driven to madness by it, and some die trying to find it, and some find it without realizing they’re looking for it. Alvar himself never finds a treasure, but as I noted, for him, the search is the treasure. At times in the strip, he comes close to settling down, but whatever is inside him drives him on, and he finds himself on the road again. He never seems lonely, but Trillo does a nice job hinting at his loneliness as he moves through the story. Alvar is usually the moral compass in the story, but, like many of the tales contained in these volumes, the irony of him doing the right thing and shepherding so many to their destinies while remaining rudderless himself is always present.  Trillo doesn’t overemphasize it, which makes it all the more tragic and gripping.

Trillo doesn’t overemphasize it, which makes it all the more tragic and gripping.

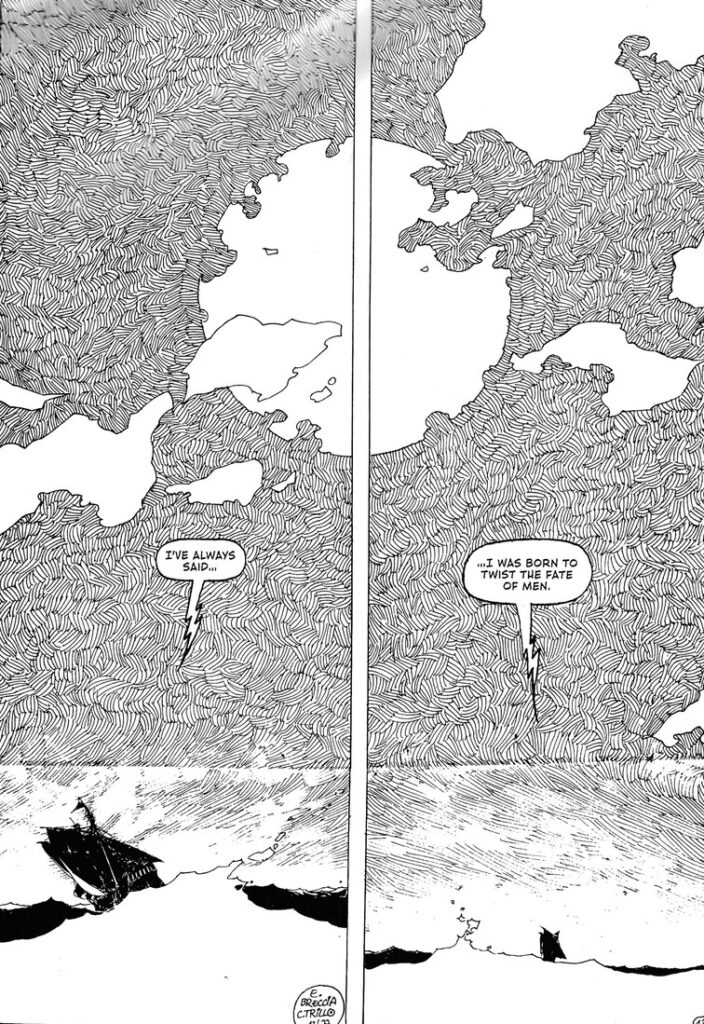

Breccia is a huge factor in the success of the strip, and it’s fascinating to look how his art evolves over the six years that he drew Alvar Mayor. Breccia is the son of Alberto Breccia, a very good artist who drew, most notably, Mort Cinder and The Eternaut, and Enrique was about a decade into his career when he started on Alvar Mayor, which was his first big solo book. The evolution of his artwork over the course of the strip’s life is startling, as he matches Trillo’s move from more realistic adventures to a more dream-like, metaphorical world very well, and it’s very neat to see. He begins with a straightforward style: heavy inks, solid lines, chunky spot blacks, good attention to detail and how clothing fits on people and what ornamentation people wore in 16th-century New Spain. He doesn’t use a lot of hatching, but he uses it well to add nice texture to the rough world Alvar and the other characters inhabit. The art is very well done, and reflects the grounded stories Trillo is telling early on in the strip.

As Trillo changes the tone of the stories, Breccia changes his artwork. Beginning with the sixth story, “The Water of Dreams” (in which Alvar has to rescue the daughter of an old man from the lord of darkness, with the help of a goddess who appears in the form of a cougar), Breccia begins to loosen up his linework and use more negative space.  The vines inside the temple of the lord of darkness are stringier and drippier than the vines we saw in earlier stories, making the scene a bit creepier as Alvar confronts the god. As the stories become a bit more dream-like, Breccia varies his line weight — Alvar’s excursions into what might be dreamworlds are drawn with a lighter touch, while Breccia also begins dropping holding lines more. He still uses heavy lines and spot blacks when he has to, of course, but the shift in the tone of the art is noticeable. He used silhouettes more often to contrast the darkness of men’s souls with the bright light of the world, and as the book becomes more about the gap between that darkness and the healing light of nature, he begins to isolate characters in large panels bereft of detail. As the book becomes more esoteric, we get some stunning panels of characters — often Alvar but not always — shrunk in size in massive panels that make them look all alone in the universe. The linework becomes scratchier, too — it does not look rushed, certainly, just a bit more ragged, as the boundaries between the real and the ethereal seems to break down a bit. Breccia uses the stark contrast between black and white very well, too — there is no shading in this book, so the blacks and whites set each other off brilliantly, as Breccia makes excellent use of them. He also uses sound effects very well, incorporating the lettering well into the artwork. Despite the work becoming a bit more impressionistic as the strip continues, Breccia’s details and characters are superb. Alvar, of course, is tall, well built, and attractive, but Breccia makes sure that over the course of the book, he always looks just a bit beaten up, because he doesn’t live a comfortable life. The other characters are a marvelous mix of beautifully drawn and caricatures, as many of the people in the book function as a Greek chorus, and Breccia always makes them odd in some way, to add some visual flair. Most of the women are beautiful, naturally, but they’re also weathered a bit, because even though the Spanish have forced their civilization on the wild land of South and Central America, the jungle is never far away, and Breccia does a nice job showing that the finery that the nobility dresses itself in is a bit shabby, as they continue to live on the very edge of heartless nature.

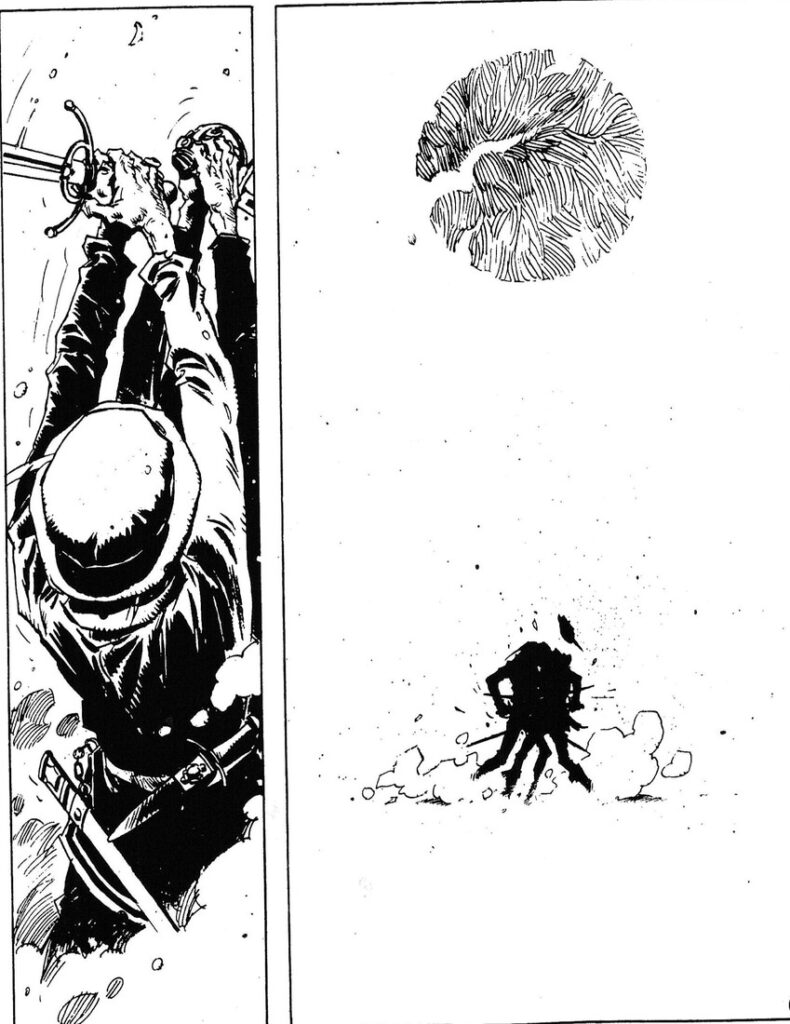

The vines inside the temple of the lord of darkness are stringier and drippier than the vines we saw in earlier stories, making the scene a bit creepier as Alvar confronts the god. As the stories become a bit more dream-like, Breccia varies his line weight — Alvar’s excursions into what might be dreamworlds are drawn with a lighter touch, while Breccia also begins dropping holding lines more. He still uses heavy lines and spot blacks when he has to, of course, but the shift in the tone of the art is noticeable. He used silhouettes more often to contrast the darkness of men’s souls with the bright light of the world, and as the book becomes more about the gap between that darkness and the healing light of nature, he begins to isolate characters in large panels bereft of detail. As the book becomes more esoteric, we get some stunning panels of characters — often Alvar but not always — shrunk in size in massive panels that make them look all alone in the universe. The linework becomes scratchier, too — it does not look rushed, certainly, just a bit more ragged, as the boundaries between the real and the ethereal seems to break down a bit. Breccia uses the stark contrast between black and white very well, too — there is no shading in this book, so the blacks and whites set each other off brilliantly, as Breccia makes excellent use of them. He also uses sound effects very well, incorporating the lettering well into the artwork. Despite the work becoming a bit more impressionistic as the strip continues, Breccia’s details and characters are superb. Alvar, of course, is tall, well built, and attractive, but Breccia makes sure that over the course of the book, he always looks just a bit beaten up, because he doesn’t live a comfortable life. The other characters are a marvelous mix of beautifully drawn and caricatures, as many of the people in the book function as a Greek chorus, and Breccia always makes them odd in some way, to add some visual flair. Most of the women are beautiful, naturally, but they’re also weathered a bit, because even though the Spanish have forced their civilization on the wild land of South and Central America, the jungle is never far away, and Breccia does a nice job showing that the finery that the nobility dresses itself in is a bit shabby, as they continue to live on the very edge of heartless nature.  He does some interesting things with page designs, as well — most notably when Alvar imprisons a man for his own safety — someone is coming to kill him — and Breccia tells the entire story in thin, vertical panels, mimicking the bars of a cage. Breccia shows some violence, but not too much — very often any killing takes place just off-panel, as he shifts the point of view to, say, a close-up of the hand holding the knife or sword rather than showing the blade pierce skin. There are a few interesting exceptions to this — in one story, “Angela,” he uses six thin panels on one level of the page to show a head getting separated from a body and spinning to the ground, and there’s a very good reason that Breccia lingers on it so much. In another story, “The Hero of Villa Rica,” a man kills his enemy, and while we only see the blade of his sword on the downstroke from the killing blow, Breccia uses five panels across two pages showing the victim collapsing, dead, as it’s such an important event in the mind of the killer, and he savors it for as long as he can. There is certainly violence in the book, and Breccia does show people fighting and the grim aftereffects of violence, but it’s not a particularly bloody book. Trillo and Breccia do a better job showing how violence eats away at people rather than showing the violence itself, and it fits nicely into the tone of the book.

He does some interesting things with page designs, as well — most notably when Alvar imprisons a man for his own safety — someone is coming to kill him — and Breccia tells the entire story in thin, vertical panels, mimicking the bars of a cage. Breccia shows some violence, but not too much — very often any killing takes place just off-panel, as he shifts the point of view to, say, a close-up of the hand holding the knife or sword rather than showing the blade pierce skin. There are a few interesting exceptions to this — in one story, “Angela,” he uses six thin panels on one level of the page to show a head getting separated from a body and spinning to the ground, and there’s a very good reason that Breccia lingers on it so much. In another story, “The Hero of Villa Rica,” a man kills his enemy, and while we only see the blade of his sword on the downstroke from the killing blow, Breccia uses five panels across two pages showing the victim collapsing, dead, as it’s such an important event in the mind of the killer, and he savors it for as long as he can. There is certainly violence in the book, and Breccia does show people fighting and the grim aftereffects of violence, but it’s not a particularly bloody book. Trillo and Breccia do a better job showing how violence eats away at people rather than showing the violence itself, and it fits nicely into the tone of the book.

Trillo and Breccia took a good adventure idea and turned it into something darker, more thoughtful, and more compelling without ever losing the adventurous parts. The book has dastardly villains, beautiful damsels in and not in distress, weird humor, some stock characters that Trillo deepens through the writing, and stunning art that brings this distant yet familiar world to life. Despite the setting and time period, Trillo never loses sight of universal human traits — lust for money, yes, but also a yearning for meaning in a world that seems determined to wrest understanding away from us. Alvar never finds a home and only finds love briefly, but he is content with his life, as he knows that what he does — search — has endless possibilities and endless victories, while those he guides, who are looking only for treasure, never figure out how to be happy. The strip ends with Alvar learning some things about his father and his time spent with Pizarro, and Trillo shows that even though his father was a decent man, Alvar has surpassed him, as he is able to resist the lure of gold. Trillo gives us a noble man among many who are not, and takes what would have been a good adventure story and turns it into a psychological masterpiece.

Alvar Mayor has been collected in four volumes by Epicenter Comics, as noted above. It appears the Spanish editions are on Amazon, but to get them in English, you have to go to Epicenter’s site or poke around a bit. They’re definitely worth the time! And be sure to check out the archives to see other selections!

Epicenter strikes again!

I’d like to read this at some point; it’s all been translated into Croatian some time ago (there is now even a complete HC edition) and they’re easy enough to find in most libraries, but the state of my shelf of shame makes me feel a bit guilty about checking them out.

Epicenter does some keen reprints, which is nice.

Ah, the shelf of shame. Mine is large and varied, but I’m working on it!

These look pretty keen, but they seem hard to come by in the Uk, at least the English language versions.

Even through EBay they are only available through American vendors and the postage is a killer, such is life.

Yeah, it seems like they are a bit difficult to find. It’s frustrating — we can keep random Venom comics in print forever, but something neat like this can go out of print too easily! 🙁