Looking back, I’m not sure it’s possible to grasp what a seismic shock Jack Kirby leaving Marvel in 1970 was at the time. There was a lot less moving between companies in those days and this was Jack Kirby moving, one of the men who’d made Marvel what it was. Marvel artist John Romita couldn’t believe Fantastic Four would go on without Kirby, let alone that Stan Lee would assign him as Kirby’s replacement. But that was the feeling of Marvelites who experienced things in real time; learning about it afterwards or watching it happen as part of my Silver Age reread, I don’t get the same feeling. I’m sure that’s partly because I’m not a massive Kirby fan. Perhaps also because I know Marvel kept going without him — indeed I read a lot more Marvel in the Bronze Age than I had in the Silver.

It’s much easier for me to connect with fans’ reactions to Kirby’s arrival at DC and the launch of his Fourth World books. If anything, I find them probably more startling now than if I’d been reading comics when Kirby debuted at DC with Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #133. The cover, for instance, was hardly shocking; past Curt Swan covers showed us Jimmy as a biker —

— and he’d frequently gone head-to-head with his pal.

Neither would the off-the-wall aspects of the opening issue have seemed out of place. As this Curt Swan cover below reminds us, Jimmy Olsen had always been a weird book.

At 12, I’m not sure it would have registered that Kirby’s wild imagination was a different kind of weird. Then again, when I read the issues with Don Rickles and the giant kryptonite Jimmy a year or two later (they came out in 1971 but I’m not sure if a friend lent them to me at the time or a lot later) I was very conscious this was bizarre stuff (I’ll get to that in a later post, I’m sure).

Then there’s Jimmy himself.

I doubt I’d have noticed at the time that Kirby wrote Jimmy as extremely competent. That happened in the Silver Age more than people credit — for all the nitwitted adventures Jimmy engaged in, a number of stories show he’s a capable reporter too — but Kirby was much more consistent about it. While much of what Kirby brought to the strip would fade away, the idea of Jimmy as a hero rather than a goofball would continue on through the Bronze Age (these days, series such as All-Star Superman and Who Killed Jimmy Olsen? play up the goofy stuff as something that makes Jimmy stand out).

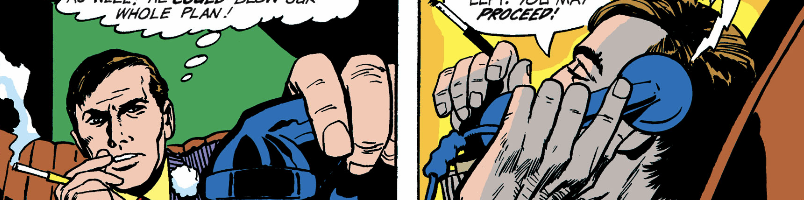

Morgan Edge, the media mogul who’d just bought the Daily Planet, would stick around too. This first issue establishes he’s working with some group called Intergang, sending them to kill Clark Kent. Astonishingly, even though Kent’s such a cowardly schmuck, he somehow survives every fricking attempt. What’s with that?

Then there’s the Newsboy Legion.

I’d never heard of them, or their parents; back then I’d have had no way of knowing if the original Newsboys ever appeared before or like the Inferior Five’s parents had been made up for the backstory. In those days, I was used to having comics reference events I’d never heard of so it wouldn’t have surprised me either way.

I certainly had no idea that Flipper Dipper was making his debut here; Kirby was ahead of the curve on realizing old all-white teams could use some diversity. Unfortunately making Flipper a scuba buff made him seem like comic relief guy, which is not a good look for the only black member. His skills do play a role in this story; when Jimmy and the kids are under fire, the attackers gloat the only way they could survive is if, say, one of them swum up a nearby river and jumped the shooters from behind. Guess what happens next?

Setting aside my personal reactions for the second, it’s clear Kirby’s trying to hit the ground running. Contrary to legend, he did not pick Jimmy Olsen because it was DC’s worst-selling book but because changes in the creative team meant he wouldn’t be taking someone else’s gig away from them. And because Carmine Infantino, who’d encouraged him to switch companies, wanted him on one of DC’s established books, preferably one of the Superman-related series (which didn’t stop DC from having Kirby’s Superman faces redrawn).

Kirby would have preferred starting from scratch with some all-new books but he gave it his all. Edge sends him and the Newsboy Legion into the Wild Area somewhere near Metropolis, riding in the souped-up Whiz Wagon —

— and explaining it’s not a place for a square like Clark.

Both in this book and Forever People, Kirby’s looking at what Kids These Days are into. Like Bob Haney and very much unlike Joe Simon, Kirby seems optimistic the kids, even hippies and dropouts, have potential. In the Wild Area this issue we meet bikers, a guru and some stuff that’s — well, take a look.

Reading now, I’m puzzled by the implication the Wild Area is just sort of sitting somewhere not far from Metropolis yet nobody’s allowed in and nobody knows what’s inside. I don’t recall any explanation in later issues (“The Mountain of Judgment blocks all overhead views from spy planes and satellites.”). Despite that, it’s an interesting opening. Although reading now, I don’t find it so interesting I’m blown away.

I doubt I’d have been blown away at the time. Kirby’s setting up a lot of stuff here and the story takes a backseat to the world building. The Wild Area’s bikers aren’t that interesting; Intergang’s killers are weird, but nothing remarkable for comics. But bigger and wilder stuff was on the way.

Having noted the launch of Jack Kirby, DC Writer-Artst, I’ll wrap up by noting some more staff changes.

“Dark City of Doom” in House of Mystery #188 was the second story for Tony deZuniga, who’d work on many DC series in the next few years as well as lots more anthology stories; I remember him mostly for being the co-creator of Black Orchid but he did a great deal more.

Writer Gerry Conway had already done more than a dozen stories in the previous year for DC and Marvel, mostly in books I don’t have available so it didn’t register. Conway would, of course, jump to full-time Marvel work before long, writing Daredevil, Spider-Man and many, many other titles at both companies. His career is a mixed bag but it was a long one and, I think, an influential one as he shaped a number of books at both companies. And this story is above average for House of Mystery and DC’s sister anthologies.

Balancing out the new kids arriving, Mort Weisinger departed, leaving Jimmy Olsen with #132. Murray Boltinoff took over Action; Julius Schwartz took over Superman and World’s Finest, turning the latter from a Batman/Superman book to Superman’s Brave and the Bold, as you can see below on Carmine Infantino’s cover.

Weisinger was from most accounts a bullying, insufferable boss to work for but most of the Superman mythos we know — the Legion of Superheroes, Supergirl, Krypto, the Phantom Zone, etc. — was developed on his watch. I don’t believe he ever grasped the idea older fans were becoming a serious part of his audience, but I have to give him credit for co-creating a lot of what makes Superman Superman.

More changes are coming as the Bronze Age moves forward.

I share you opinion that – even if I had been of the proper age when Kirby’s Jimmy Olsen hit the spinner racks – it probably wouldn’t have blown my mind. I mean, it didn’t when I later did get around to reading it. However, I really like the concept of Jimmy being a sort of rugged adventurer with a sweet ride and a team of (mostly) capable assistants – almost like a junior version of Doc Savage and his crew.