Yes, it’s an Alan Moore comic. It’s almost like the dude is good at writing comics or something!

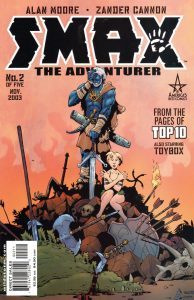

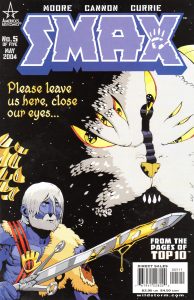

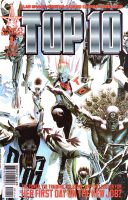

Top 10 by Alan Moore (writer), Gene Ha (artist, issues #1-12, The Forty-Niners), Zander Cannon (layouts, issues #1-12; penciller, Smax #1-5; inker, Smax #1), Andrew Currie (inker, Smax #2-5), Richard Friend (inker, Smax #5), Wildstorm FX (colorist, issues #1-9, Smax #4-5), Alex Sinclair (colorist, issues #10-12), Ben Dimagmaliw (colorist, Smax #1-3), Art Lyon (colorist, The Forty-Niners), and Todd Klein (letterer).

Published by DC/Wildstorm/America’s Best Comics, 17 issues (Top 10 #1-12 and Smax #1-5) and one graphic novel (The Forty-Niners), cover dated September 1999 – October 2001 (Top 10), October 2003 – May 2004 (Smax), and 2005 (The Forty-Niners).

For a lot of people, Alan Moore’s renaissance began in 1999 when he launched America’s Best Comics and its titles, after he had spent a good chunk of the 1990s in the wasteland writing WildC.A.T.s and other such stuff (although his WildC.A.T.s run is pretty darned good – he’s Alan Moore, after all). ABC was full of good comics, but of those, Top 10 is the only one that really stands out as great. Tom Strong is fun adventure stuff, Tomorrow Stories varies in quality, Promethea is Moore deciding he’s smarter than everyone else, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen quickly became less about what was happening and more about how many references Moore could cram into it (which bedevils Top 10 just a tiny bit, as well).  But Top 10 hits that sweet spot that Moore is so good at – it feels more consequential than Tom Strong and Tomorrow Stories. far less pedantic than Promethea, and a hell of a lot less rape-y than LoEG (although it’s still a little rape-y – it’s Alan Moore, after all!). Moore takes something mundane – a police procedural – and makes it fantastic while keeping it grounded. He’s amazing at that kind of thing, which is why this comic works so well. It’s also humanistic, clever without being smart-ass, and funnier than you might think. Moore has a great sense of humor, which he rarely lets show in his work, but Top 10 (and Smax, which is funnier than the main title) are good examples of how funny he can be when he’s not, you know, being all rape-y.

But Top 10 hits that sweet spot that Moore is so good at – it feels more consequential than Tom Strong and Tomorrow Stories. far less pedantic than Promethea, and a hell of a lot less rape-y than LoEG (although it’s still a little rape-y – it’s Alan Moore, after all!). Moore takes something mundane – a police procedural – and makes it fantastic while keeping it grounded. He’s amazing at that kind of thing, which is why this comic works so well. It’s also humanistic, clever without being smart-ass, and funnier than you might think. Moore has a great sense of humor, which he rarely lets show in his work, but Top 10 (and Smax, which is funnier than the main title) are good examples of how funny he can be when he’s not, you know, being all rape-y.

In Top 10, Moore takes a fairly common conceit and adds his own sense of genius to it, which is why it works so well. He creates Neopolis, a city in which everyone has some kind of power. It’s basically a ghetto, where the powers-that-be placed everyone with powers so they didn’t destroy the rest of the country, but Moore wisely doesn’t bring that to the forefront of the story. Many people in the letters column pointed out its similarity to Astro City, mainly because Moore takes a down-to-earth approach to superpowered people (of course, not everyone in Astro City has powers, so the comparison isn’t that apt), but that’s something Moore has done his entire career. What makes Top 10 such a great comic is that he gives everyone powers, figures that someone needs to police the populace, and then gives us “regular” cops – yes, they have powers, but they have to deal with bureaucracy and annoying suspects and rapacious lawyers and struggles with paying bills and personality conflicts.  The cops of the tenth precinct (all of this world’s Neopolis is one precinct, as each Neopolis of each dimension is a different precinct) go about their jobs, following leads, trying to make links between random events (some of which exist, and some of which don’t), and simply attempting to keep things even-keeled. Moore has always done a very good job of making the fantastical mundane, and the contrast between all these people with their amazing powers and the occasional tedium of their lives gives the book some nice tension and a good deal of its humor. It’s a very smart way to present the book.

The cops of the tenth precinct (all of this world’s Neopolis is one precinct, as each Neopolis of each dimension is a different precinct) go about their jobs, following leads, trying to make links between random events (some of which exist, and some of which don’t), and simply attempting to keep things even-keeled. Moore has always done a very good job of making the fantastical mundane, and the contrast between all these people with their amazing powers and the occasional tedium of their lives gives the book some nice tension and a good deal of its humor. It’s a very smart way to present the book.

Moore also introduces a new police officer, Robyn Slinger, to be our point-of-view character. This is another trope that works well, and Robyn is the nominal star of the book (even though it’s a true ensemble, Robyn seems to always be able to help out in crucial ways). She is partnered with Jeff Smax, a surly giant who, it turns out, has hidden depths (as we discover not only throughout the book but in Smax, the spin-off mini-series in which he and Robyn go to his home dimension). Despite Robyn’s role in the book, Moore writes dozens of characters, as the cops go about their days, and each one of them is fascinating. Moore has always been good at creating interesting characters almost instantly, and because of the conceit of the book – that these characters are just working stiffs – we get to see them in every situation, so Moore avoids the “superhero” dialogue that can sound stilted and rehearsed.  The book takes place over a few weeks – the first issue tells us it’s 5 October 1999, while the last date we know definitely is the following Wednesday, the 14th – and Moore gives us almost an hour-by-hour breakdown of what’s going on, so the police aren’t always out working on exciting cases. Obviously, they get some exciting and interesting cases – the first murder in the book is a complicated affair that spans dimensions and isn’t resolved until issue #10, when we actually get a big superhero/supervillain battle – but we also get the more mundane stuff, from a domestic disturbance to the mouse infestation in Officer Duane Bodine’s mother’s apartment (which, because even the mice in Neopolis have powers, escalates hilariously). Robyn is one of the most grounded and “normal” characters in the book – her power involves using small toys that she can mentally control to do tasks – so it’s also a good idea to use her as the POV character. Her father was a police officer in the 1940s, and he appears in The Forty-Niners, the graphic novel about the first days of Neopolis, so it’s a nice link between the two separate stories (Captain Traynor, the protagonist of The Forty-Niners, is the boss at Precinct Ten in the series, so that’s another link).

The book takes place over a few weeks – the first issue tells us it’s 5 October 1999, while the last date we know definitely is the following Wednesday, the 14th – and Moore gives us almost an hour-by-hour breakdown of what’s going on, so the police aren’t always out working on exciting cases. Obviously, they get some exciting and interesting cases – the first murder in the book is a complicated affair that spans dimensions and isn’t resolved until issue #10, when we actually get a big superhero/supervillain battle – but we also get the more mundane stuff, from a domestic disturbance to the mouse infestation in Officer Duane Bodine’s mother’s apartment (which, because even the mice in Neopolis have powers, escalates hilariously). Robyn is one of the most grounded and “normal” characters in the book – her power involves using small toys that she can mentally control to do tasks – so it’s also a good idea to use her as the POV character. Her father was a police officer in the 1940s, and he appears in The Forty-Niners, the graphic novel about the first days of Neopolis, so it’s a nice link between the two separate stories (Captain Traynor, the protagonist of The Forty-Niners, is the boss at Precinct Ten in the series, so that’s another link).

The cases in Top 10 are, as I noted, typical police cases, but with the twist that superpowers are involved. The first call Robyn and Smax get is a domestic disturbance involving a guy who can stretch (like Reed Richards), which comes in handy if you want to strangle someone. The first murder, of a guy dressed like a cowboy, is the one that takes ten issues to solve, but early on, one of the cops, Synaesthesia Jackson, uses her senses (synethesia is the condition by which you interpret an impression – like a noise – with a different sensory organ, so you “see” noises as colors) to find an important clue.  At the beginning of the series, the police are already embroiled in the Libra case – a serial killer who strikes during October, and one who apparently has been menacing the city for some years. Libra kills prostitutes and street people, and the identity of the killer is another twist on Moore’s conceit, as the killer could only exist in this kind of universe. Someone is running around grabbing women’s asses, and of course it’s a “ghost,” which makes sense in the world of Neopolis. Smax arrests a small, Godzilla-looking creature whose dad is a gigantic, Godzilla-looking creature … who drinks a lot. Not a good combination. There’s a powerful “psychokinetic” who believes he’s Santa Claus, which means he can cause things to fly and, of course, drop, so he’s hard to stop. The police try to solve Baldur’s murder in issue #7, the funniest story of the run. Even traffic accidents are bizarre, as two different “flyers” try to teleport into the same space in issue #8, with predictably tragic results. Through it all, though, Moore keeps the focus on the mundane – the traffic accident is just that, there’s a pornography ring, there are drugs and what lengths people will go to get them. He does a nice job linking some of the cases, or having one lead into another, but generally it’s just good, solid police work … with superpowers.

At the beginning of the series, the police are already embroiled in the Libra case – a serial killer who strikes during October, and one who apparently has been menacing the city for some years. Libra kills prostitutes and street people, and the identity of the killer is another twist on Moore’s conceit, as the killer could only exist in this kind of universe. Someone is running around grabbing women’s asses, and of course it’s a “ghost,” which makes sense in the world of Neopolis. Smax arrests a small, Godzilla-looking creature whose dad is a gigantic, Godzilla-looking creature … who drinks a lot. Not a good combination. There’s a powerful “psychokinetic” who believes he’s Santa Claus, which means he can cause things to fly and, of course, drop, so he’s hard to stop. The police try to solve Baldur’s murder in issue #7, the funniest story of the run. Even traffic accidents are bizarre, as two different “flyers” try to teleport into the same space in issue #8, with predictably tragic results. Through it all, though, Moore keeps the focus on the mundane – the traffic accident is just that, there’s a pornography ring, there are drugs and what lengths people will go to get them. He does a nice job linking some of the cases, or having one lead into another, but generally it’s just good, solid police work … with superpowers.

The superpowered stuff is just window dressing, ultimately. Moore can write brilliant superheroes in his sleep, and he uses them in Top 10 as a bit of a distraction. They’re the “fun” part of the book – look at all the weird powers Moore can come up with! – and they let Moore get into his real themes, which is more about society and how it functions. Moore has always been one of the most socially conscious comics writers, and he examines Neopolis society – and beyond – by turning the characters into very real people with very real issues.  Even though Neopolis is not only the height of modernity, but the height of futurity, too, its inhabitants are still people, and the way they react to others and situations makes the tension in the book even more fraught. Moore is fascinated (some might say obsessed) with sexuality and our reaction to it, so he introduces Jackie Kowalski, a lesbian, early on. She vaguely hits on Robyn in issue #1, but Robyn rebuffs her as politely as she can. The men in the book are generally bummed that Jackie is gay (she’s quite attractive), but at least she’s open about it. Steve Traynor, the captain of the precinct, is gay, and apparently the cops under his command don’t know it (he’s not in the closet, exactly, as he lives with his long-time partner, but it’s clear those who work for him don’t know). Traynor’s sexuality is a big plot point in The Forty-Niners, which takes place in 1949, so of course attitudes were a bit more stringent (although Moore does subtly suggest that many in 1949 were more accepting of homosexuality than those in the present, as long as it wasn’t too obvious). In Smax, the spin-off mini-series in which Smax and Robyn go to Smax’s home dimension, we get an entire incest story that ends happily. Moore does look askance at the practice of teen sidekicks, noting that it’s a bit too close to sexual abuse, but he’s not unique in that regard. It’s interesting that even in 1999-2001, when Moore wrote these issues, there was still in our society a stigma against homosexuality, as Traynor’s case is clearly something Moore believed happened in the “real world.” Jackie’s sexuality is grudgingly tolerated, possibly because she’s a woman and that’s “hot” or the men just figured they could “convert” her. Traynor’s sexuality has to remain hidden.

Even though Neopolis is not only the height of modernity, but the height of futurity, too, its inhabitants are still people, and the way they react to others and situations makes the tension in the book even more fraught. Moore is fascinated (some might say obsessed) with sexuality and our reaction to it, so he introduces Jackie Kowalski, a lesbian, early on. She vaguely hits on Robyn in issue #1, but Robyn rebuffs her as politely as she can. The men in the book are generally bummed that Jackie is gay (she’s quite attractive), but at least she’s open about it. Steve Traynor, the captain of the precinct, is gay, and apparently the cops under his command don’t know it (he’s not in the closet, exactly, as he lives with his long-time partner, but it’s clear those who work for him don’t know). Traynor’s sexuality is a big plot point in The Forty-Niners, which takes place in 1949, so of course attitudes were a bit more stringent (although Moore does subtly suggest that many in 1949 were more accepting of homosexuality than those in the present, as long as it wasn’t too obvious). In Smax, the spin-off mini-series in which Smax and Robyn go to Smax’s home dimension, we get an entire incest story that ends happily. Moore does look askance at the practice of teen sidekicks, noting that it’s a bit too close to sexual abuse, but he’s not unique in that regard. It’s interesting that even in 1999-2001, when Moore wrote these issues, there was still in our society a stigma against homosexuality, as Traynor’s case is clearly something Moore believed happened in the “real world.” Jackie’s sexuality is grudgingly tolerated, possibly because she’s a woman and that’s “hot” or the men just figured they could “convert” her. Traynor’s sexuality has to remain hidden.  Moore adds another layer of irony to the situation because Traynor, after seeing sidekicks get abused in the present, reminds his partner that when they got together, Traynor was only 16 and his partner was 24. As usual with Moore, there are no easy answers.

Moore adds another layer of irony to the situation because Traynor, after seeing sidekicks get abused in the present, reminds his partner that when they got together, Traynor was only 16 and his partner was 24. As usual with Moore, there are no easy answers.

Moore doesn’t stop with sexuality, though. He uses the book, as he often does, to examine other prejudices in society. Early on, he indicates that prejudice against robots is very real, and even some cops share this prejudice. This comes to a head after one of the cops is killed in issue #10 and, one issue later, an android replacement comes on board. The cops have to confront their own prejudices, and Moore does a nice job with it. In the course of one investigation, a cop named King Peacock has to travel to the main dimension following a lead. It’s a place where the Roman Empire remained the world’s power, and the people are wildly racist, which makes it more difficult for John Corbeau – King Peacock – because he’s black (or “Nubian,” as they insist on calling him). Jeff Smax exhibits prejudice toward his own home, because it’s such a backwater. He and his twin sister have been incestuous for years, which is perfectly normal in his dimension but which he now regards his embarrassment because he’s been out in the big world, where it’s frowned upon. Instead of dealing with it like an adult, he just denigrates everything about his home (which is a “cute,” “cartoony” place that Moore, naturally, makes realistic by tweaking it just enough). The Forty-Niners focuses on prejudice a bit more, as a crucial plot point has to do with Slavs entering the city in the aftermath of World War II. Moore makes them all vampires, which is a nod to the conventions of the genre, but even though they are dangerous, the way some of the “heroes” speak about them is tinged with racial prejudice – one even says that there’s such a thing as being “too white,” which implies that “white” is good, but “Slavs” (that is, the vampires) aren’t “real” white people. In a brief moment, we learn that one cop’s – Irma Wornow – husband is unemployed because he’s precognitive, and laws exist keeping them from many jobs. This codified prejudice is just another interesting aspect of life in Neopolis, where the marvels of technology can’t overcome human bias. Even Libra’s lawyer argues that the killings are a genetic predisposition, and the police are too prejudiced to see that. Moore has some fun with the conceit – one lawyer (not Libra’s) is a literal shark-man, and while I don’t know if Moore has any personal animus against lawyer, I imagine his legal dust-ups with DC Comics hasn’t made him particularly well-disposed toward them. Moore rarely hammers home these points, allowing them to flow from the interactions between the characters, which makes them more potent and real.

Of course, given that it’s Alan Moore, the stories aren’t just about social commentary, because Moore can write superhero stories like nobody’s business. He thinks about what superheroes in a “real world” setting would be like, which makes his stories much deeper and far more interesting than your usual superhero fare.  What might happen if the United States offered sanctuary to Nazi scientists after the war in exchange for their help in building Neopolis? How would a fantasy world actually work? Why would a certain police officer wear clothes, and why would that cause problems with her boss? What would sexually-transmitted diseases in a city full of superpowered people do to those people? How would superpowered mice and superpowered cats resolve their conflict? How do you solve a murder involving a deity? Moore takes the time to ponder how people would respond to these situations, not in rote ways, but in ways that fit their characters. So everyone responds a bit differently, which makes the book much more lively than a regular superhero book. Too many characters (not just superheroes and not just in comics) act in a way that fits the plot, while Moore’s characters act in the way that fits them. Even if the readers don’t know much about them yet, we can glean parts of their personalities just by the way they’re acting. A struggle to create characters comes from trying to shoehorn them into a particular plot. Moore comes up with plots, true, but he doesn’t try to cram the personalities of his characters into that plot. He lets them react the way they would, and this makes them unique.

What might happen if the United States offered sanctuary to Nazi scientists after the war in exchange for their help in building Neopolis? How would a fantasy world actually work? Why would a certain police officer wear clothes, and why would that cause problems with her boss? What would sexually-transmitted diseases in a city full of superpowered people do to those people? How would superpowered mice and superpowered cats resolve their conflict? How do you solve a murder involving a deity? Moore takes the time to ponder how people would respond to these situations, not in rote ways, but in ways that fit their characters. So everyone responds a bit differently, which makes the book much more lively than a regular superhero book. Too many characters (not just superheroes and not just in comics) act in a way that fits the plot, while Moore’s characters act in the way that fits them. Even if the readers don’t know much about them yet, we can glean parts of their personalities just by the way they’re acting. A struggle to create characters comes from trying to shoehorn them into a particular plot. Moore comes up with plots, true, but he doesn’t try to cram the personalities of his characters into that plot. He lets them react the way they would, and this makes them unique.

I imagine a lot of artists want to work with Moore, despite some of the issues he’s had with artists in the past, because he gives them such meaty things to draw.  I also wonder about the way certain artists “fit” the story and others don’t. Gene Ha drew all 12 issues of Top 10 and The Forty-Niners, but he didn’t draw Smax, as Zander Cannon stepped in for that. Was Ha busy with other things when Smax was coming out (I don’t know how long The Forty-Niners took him, but his art on the book is more refined than on the regular series, and it just looks like it took him a while), or did Moore want someone else for the series? Cannon seems to “fit” Smax better than Ha would – his rounded, more cartoony art works really well for the fantasy world where Smax grew up, and his dragon is oddly perfect – it doesn’t conform to what we think of as a dragon, but it’s still terrifying yet strangely cuddly, which is a good thing for such a bizarre world. Yet Cannon, who is credited with “art” on the first five issues of Top 10 and with “layouts” after that, leading me to believe he did layouts for the entire series, would not work on the regular series very well. Ha’s more angular, detailed, and precise artwork is wonderfully matched to the futurism of Neopolis. Moore has a reputation for being very detailed in his scripts, so I imagine Ha had some help from him, but he still designs hundreds of amazing characters, each beautifully recognizable. The first page of the series is a perfect example of this. Robyn sits on the train, heading for her first day of work, and she doesn’t move from her seat as people get on and off the train in each panel. Ha shifts her legs in each panel just to show that she’s adjusting to the tired spots on her body, but other than that, she doesn’t move. The people flow around her, some wearing costumes, some not, some in decent shape, some portly, but all rendered precisely.

I also wonder about the way certain artists “fit” the story and others don’t. Gene Ha drew all 12 issues of Top 10 and The Forty-Niners, but he didn’t draw Smax, as Zander Cannon stepped in for that. Was Ha busy with other things when Smax was coming out (I don’t know how long The Forty-Niners took him, but his art on the book is more refined than on the regular series, and it just looks like it took him a while), or did Moore want someone else for the series? Cannon seems to “fit” Smax better than Ha would – his rounded, more cartoony art works really well for the fantasy world where Smax grew up, and his dragon is oddly perfect – it doesn’t conform to what we think of as a dragon, but it’s still terrifying yet strangely cuddly, which is a good thing for such a bizarre world. Yet Cannon, who is credited with “art” on the first five issues of Top 10 and with “layouts” after that, leading me to believe he did layouts for the entire series, would not work on the regular series very well. Ha’s more angular, detailed, and precise artwork is wonderfully matched to the futurism of Neopolis. Moore has a reputation for being very detailed in his scripts, so I imagine Ha had some help from him, but he still designs hundreds of amazing characters, each beautifully recognizable. The first page of the series is a perfect example of this. Robyn sits on the train, heading for her first day of work, and she doesn’t move from her seat as people get on and off the train in each panel. Ha shifts her legs in each panel just to show that she’s adjusting to the tired spots on her body, but other than that, she doesn’t move. The people flow around her, some wearing costumes, some not, some in decent shape, some portly, but all rendered precisely.  Ha gives the police an easy camaraderie that Moore puts in their words but which is harder to do in their faces, but Ha shows that these are people who might not all be friends but who know how to work and joke together. Even his relatively minor characters, like Janus, the two-faced telephone operator at the precinct (her faces look both forward and back!), are completely and thoughtfully brought to life. Ha has to create not only a lot of characters, he has to put a lot in costume and show their powers occasionally, which adds to the difficulty of drawing the series. Moore loves to add random characters who have nothing to do with the narrative, and Ha has to draw all of them, as well, and he also has to put in all the advertisements that Moore likes to include in his comics. Plus, the splash page in issue #9, when Duane confronts the mice in his mother’s apartment, is one of the great sight gags in comics history. Ha not only gives us the majesty of Neopolis, he and Moore don’t forget that it’s a city, and Ha gives us excellent seedy areas of town, as well. When he has to draw something truly horrific, he’s excellent at that, too. Ha’s thin line and attention to detail makes the world Moore envisions come to life in a way that many artists would be unable to do, and while it probably made the book take a bit longer to come out (12 issues took almost 2 years to come out, although I have no idea if Moore or Ha was responsible for the delay), it makes it a great, unified reading experience. Moore’s somewhat annoying penchant for adding pop culture characters into the background isn’t in as much evidence here as it is in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, but Ha still does a good job when Marvin the Martian and Asterix and Obelix show up.

Ha gives the police an easy camaraderie that Moore puts in their words but which is harder to do in their faces, but Ha shows that these are people who might not all be friends but who know how to work and joke together. Even his relatively minor characters, like Janus, the two-faced telephone operator at the precinct (her faces look both forward and back!), are completely and thoughtfully brought to life. Ha has to create not only a lot of characters, he has to put a lot in costume and show their powers occasionally, which adds to the difficulty of drawing the series. Moore loves to add random characters who have nothing to do with the narrative, and Ha has to draw all of them, as well, and he also has to put in all the advertisements that Moore likes to include in his comics. Plus, the splash page in issue #9, when Duane confronts the mice in his mother’s apartment, is one of the great sight gags in comics history. Ha not only gives us the majesty of Neopolis, he and Moore don’t forget that it’s a city, and Ha gives us excellent seedy areas of town, as well. When he has to draw something truly horrific, he’s excellent at that, too. Ha’s thin line and attention to detail makes the world Moore envisions come to life in a way that many artists would be unable to do, and while it probably made the book take a bit longer to come out (12 issues took almost 2 years to come out, although I have no idea if Moore or Ha was responsible for the delay), it makes it a great, unified reading experience. Moore’s somewhat annoying penchant for adding pop culture characters into the background isn’t in as much evidence here as it is in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, but Ha still does a good job when Marvin the Martian and Asterix and Obelix show up.  In The Forty-Niners, Art Lyons uses digital painting to soften Ha’s pencils just a bit, adding more coloring nuances and making the sepia-toned world feel older and more innocent, even though it obviously isn’t. Ha does a nice job making everything look just a bit less technological, with more steampunk and baroque elements, so even though Neopolis is still ahead of the “real” tech of 1949, it feels like people are still experimenting with how to integrate the new technology into the older, more staid world – a Rocketeer helmet radio stands alongside Hummel figurines in one panel, for instance. It’s a nice nostalgic feeling in the artwork, even as Ha and Moore are telling a story about looking to the future. I’ve already written about Todd Klein’s lettering in my post about Sandman, but of course he’s the underrated genius on this book, as so many people speak differently, and Klein does a superb job making it clear how their voices “sound” just through the way he creates the letters. A comic is greatly enhanced by great lettering, people!

In The Forty-Niners, Art Lyons uses digital painting to soften Ha’s pencils just a bit, adding more coloring nuances and making the sepia-toned world feel older and more innocent, even though it obviously isn’t. Ha does a nice job making everything look just a bit less technological, with more steampunk and baroque elements, so even though Neopolis is still ahead of the “real” tech of 1949, it feels like people are still experimenting with how to integrate the new technology into the older, more staid world – a Rocketeer helmet radio stands alongside Hummel figurines in one panel, for instance. It’s a nice nostalgic feeling in the artwork, even as Ha and Moore are telling a story about looking to the future. I’ve already written about Todd Klein’s lettering in my post about Sandman, but of course he’s the underrated genius on this book, as so many people speak differently, and Klein does a superb job making it clear how their voices “sound” just through the way he creates the letters. A comic is greatly enhanced by great lettering, people!

Moore wrapped up all the storylines in Top 10, so I’m not sure if it ended when he wanted it to (at the end of issue #12, we get notes about both Smax and The Forty-Niners – both promised in 2002, which didn’t happen) or if outside influences kept him from continuing, but it feels as complete as it can be. Obviously, these characters could easily support many more stories, but Moore does a good job wrapping his plot threads up. Top 10 was tough to read in installments (which I did) because of the length of time between issues and Moore’s dense plotting, but reading it in one or a few sittings is a wonderfully rewarding experience.  It’s a beautifully-written and expertly-drawn superpower book, with Moore’s typical brilliant plotting and characterization, but with more humor than he had shown in a while (to be fair, a lot of the ABC books – LoEG excepted – had their moments of humor). I haven’t read his recent Avatar work, but it seems like Top 10 is, right now, the last great comic that Moore has written, as he slowly leaves them behind. (His recent LoEG stuff is fine, but not great, although his brief short stories in Cinema Purgatorio have been eerily superb.) You can find the entire run in a handy trade (see the link below!), and while Smax is difficult to find in trade (I guess it fell out of print and hasn’t been reissued), you can still find the single issues around, and The Forty-Niners is also easy to find. It’s a lot of fun to read, but of course, with Moore, there’s so much more going on beneath the surface that it takes a few readings to absorb everything that’s happening. That’s always fun to do, though!

It’s a beautifully-written and expertly-drawn superpower book, with Moore’s typical brilliant plotting and characterization, but with more humor than he had shown in a while (to be fair, a lot of the ABC books – LoEG excepted – had their moments of humor). I haven’t read his recent Avatar work, but it seems like Top 10 is, right now, the last great comic that Moore has written, as he slowly leaves them behind. (His recent LoEG stuff is fine, but not great, although his brief short stories in Cinema Purgatorio have been eerily superb.) You can find the entire run in a handy trade (see the link below!), and while Smax is difficult to find in trade (I guess it fell out of print and hasn’t been reissued), you can still find the single issues around, and The Forty-Niners is also easy to find. It’s a lot of fun to read, but of course, with Moore, there’s so much more going on beneath the surface that it takes a few readings to absorb everything that’s happening. That’s always fun to do, though!

I still don’t have enough Comics You Should Own posted here at the blog (this is only my third) to create an archive, although probably after my next one (whatever and whenever that is!) to make one. I’m still trying to figure out how to move the old ones over here, but I’ll get to it eventually! I hope everyone enjoys reading this, if they feel like it!

So totally agree with pretty much everything you said here. I love this series and have read it all the way through twice so far (I have it all, Smax included, in trades).

By the way, I think that it should be read the first time in the order of publication, i.e., the original 12-issue series and then the follow-ups, but it’s actually better to read it again in the order of its internal chronology, meaning start with 49-ers and then go on to the regular series.

You’re right that Moore et al. did some fantastic world-building in Top 10, and theoretically many great stories could be told using the setting. However, I would not recommend the Top 10 stories not written by Moore. I read Beyond the Farthest Precinct a few years back, and frankly wish I hadn’t (not even Ordway’s art could save that one). Based on that, I’m not even remotely interested in Season Two.

And finally: that link to your old CSBG column, in the old format and with all comments intact. How…? And how do we find other old content like that?

Edo: I forgot about Beyond the Farthest Precinct and Season Two, because I knew they weren’t written by Moore and therefore I had no interest. Zander Cannon actually isn’t a bad writer – he’s done some neat graphic novels – but I doubt if anyone can take Moore’s concepts and do any kind of justice to them.

I like your idea of reading The Forty-Niners first, because it does provide some good context for the regular series. Next time I read this I think I’ll start there!

Finding the old format is convoluted, to say the least. I don’t like to link to the “new Coke” format of CBR, so I Google the post, find the date I posted it on CBR, then Google (I should bookmark it!) “wayback machine,” which takes you to the archived internet stuff. I type in the old blog’s URL, and it gives you dates when a “snapshot” was taken. Then I go to the date that’s closest to the date of the post and find it. It’s not perfect – on some of them, the images don’t work anymore – but it’s a lot better than linking to CBR, with its adverts and other horrible stuff!

Thanks for the tip, I already gave it a shot and found some of the posts in their original form (among the many things I hate about the new CBR is that the site only archived the posts without the comments, which are often quite interesting and/or fun). The best I could do before was visit the really old, pre-CBR CSBG which is all still up in its blogspot glory. Of course, it stops somewhere in early 2007.

Part of the reason I started linking to the posts through the wayback machine is because the comments are still there. I might even forgive the terrible format of the new CBR if they had kept the comments!

I’ve sung Top 10’s praises since it came out. Just a really entertaining series, on all levels. I love the sight gags peppered throughout, like the Wacky Racers in traffic, along with the Oz characters, Harry Potter, and a Blade Runner police spinner; or, a scene at a hospital where you see the Tom Baker Doctor Who consulting with Dr Fate. Or a Celestial head, as part of city architecture, or Kirby Krakle cereal. The Atomicats vs Ultramice is a scream, especially since the mice are characters like Mighty Mouse and Dangermouse.

Gene Ha was not a fast artist and was also working on Starman, occasionally (the Times Past stories). The art on The Forty-Niners did take a long time. Xander Cannon is also a favorite for The Replacement God and I loved his stuff on Smax, with things like the Harvey characters as juvenile delinquents, Smurf houses, and the Glaive, from Krull, on a mountain of weapons (aping a Frazetta Conan piece and including Kull’s axe).

I don’t see Traynor as closeted, just private about his personal life. A station captain has to maintain a certain distance from his officers and he wouldn’t be likely to present his private life in that scenario, hetero or homosexual. It would be different if he was partnered with someone and was secretive about it. I think it just reflected the character as being “The Captain,” they guy they report to and not a drinking buddy.

By the way, The Forty-Niners continues the great easter eggs, with stuff from old comic strips and media of the era. You see the Pogo characters as actual animals, which looks really weird.

Yes, the sight-gags/Easter eggs peppered throughout are yet another thing that make this so much fun to read repeatedly – I know I missed quite a few things in my first reading which I then spotted the second time around (and now I’m kind of itching to read it again…)

I don’t mind the references quite as much as I do in LoEG, but I still don’t love them too much. In the League, I feel they get in the way of the storytelling a bit, while in Top 10, they’re just background stuff and it you don’t get them, it doesn’t matter. But yes, it can be fun spotting them!

I like your explanation about Traynor, but I just found it odd that one of the characters would threaten to tell the precinct about it. It just makes it seem like it’s a bit more of a societal stigma and less of an idea about being “the captain,” who shouldn’t, in the eyes of the regular cops, have a private life. Your explanation makes sense, but I wonder if Moore was implying a bit more about it.

I’ve read this series and every thing that Mr. Moore created and wrote under the ABC imprint. I didn’t like all of them, but Top Ten, LOEG, and Promethea remains my favorites.

I didn’t bother to read the books that weren’t written by Mr. Moore, except for Greyshirt by Rick Veitch.

One of the things that I found interesting about ABC was how Mr. Moore ended up writing for DC Comics again, after Jim Lee sold the Wildstorm Imprint to DC – was that I heard that DC created a shell holding just to pay Mr. Moore.

Apparently, he was ok with DC publishing his ABC books as long as the words “DC Comics” did not appear anywhere on/in his books. I wondered if that was true.

Tom: I think that’s true. He was willing to work for them for a few years, after all, until they started censoring his books again. I’m not sure about all the legal stuff, but I’m pretty sure Jim Lee promised him that DC wouldn’t interfere with him. When they did, he took his toys and went home … again! 🙂